|

Click here to return to the main site. Battlestar Galactica: Influences Just like the best of written science fiction, Galactica is open to many interpretations, its combination of the purely visual and metaphysical and its exploration of cosmology and ontology made for a rich brew which attempted to explore the religious and philosophical monoliths which at the same time unite and divide us as a race. A contextual or deterministic examination of the show would fill a book. However, over the course of three articles, Charles Packer hopes to give a glimpse of where Galactica came from, its reflection on what it is to be human and the technical tricks it used along the way...

It has been long held that any good work of fiction, written or broadcast, should do more than just entertain, it should at the same time challenge or inform its audience, a premise which was at the heart of the new Galactica, which strove, in equal amounts to both entertain and challenge its audience. Overall it was something which it was fairly successful at doing; it had the least number of weak stand alone shows of any series. However this challenging stance didn’t spring out of nowhere.

England, on the other hand, had a wider tradition of dystopian literature and television which was born of the horrors of trench warfare and aerial bombardment. Both of which had been so ominously predicted by H.G. Wells in The Shape of Things to Come (Pub. 1933), which itself was made into an equally grim film (1936) with a script from Wells, though it did end happily for humanity, sort of. Even in 1895, when he wrote The Time Machine, he envisioned, what was left of mankind, alone in the universe, degenerated, confined to a dying planet. The English writers who followed Wells also leant towards the dystopian in their visual prophesies of the future, 1984 (BBC 1954) The Quatermass Experiment (1953), Blake’s 7 (1978), Threads (1984) and The Last Train (1999) are good examples of an outlook which although far from completely negative mostly leaned in this direction.

This didn’t just affect science fiction, but many differing genres including westerns and detective stories. Although John Ford was able to rehabilitate the western in the earlier part of the twentieth century, it wasn’t until the advent of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001 (1968) and A Clockwork Orange (1971) that audiences really started to view science fiction as something other than escapist fantasy. After this time American science fiction split into two camps. On the one hand the escapist stories of Star Trek kept the show popular, whilst at the same time allowing character driven shows like Babylon 5 (1993) to be created, though it was notable that networks preferred the former to the latter. The original Battlestar Galactica (1978) and especially its follow up show Galactica 80 (1980) was in the mould of unrealistically, tonally, hopeful shows, it was also more than a little camp, given that the majority of humanity had been wiped out. This was not an issue of the show's age, as we have seen previous writers and directors had chosen to present a much bleaker view of the future. Moore’s re-imagining dispensed with this unrealistic outlook and his show would drag humanity through hell and back, throwing a mirror up to both the angels and demons in us all.

In Moore’s Galactica they became something more, here it is mankind who steals the fire from the gods and creates thinking beings as a slave race - their creation is dealt with in the prequel show Caprica (2009) - a race that finally turns on their creators, winning their freedom after a bloody war. When the miniseries opened the truce had lasted for forty years. Moore changed little of the original premise, having the surviving remnants of the twelve human colonies gathered together, in whatever ships they could find, the eponymous ‘Rag-Tag Fleet’, and under the protection of the last surviving Battlestar - Galactica - they set off to traverse the inhospitable spaces between the stars in search of the thirteenth tribe who have been lost to time and legend, on a planet, known only as Earth. To pull in an audience which were fans of the original the decision was made to substantially reuse ships which had appeared in the seventies show.

What brought the fifties paranoia back to American television was not only the events of 9/11, but the preceding cases of American citizens attacking their own Government, which gave rise to a different aesthetic, in modern television, the aesthetic of an uber- grim reality, which itself is just as artificial as the generally hopeful aesthetic which it replaced.

Moore was far from a novice in this genre having previously worked on Star Trek: The Next Generation (1988), Deep Space Nine (1994) and Voyager (1999) before being approached by David Eick (Bionic Woman (2007)) to produce a new miniseries for Universal. Moore preferred to think of this as a re-imagining, rather than a remake, a slight point but one which would allow him to take the best parts of the original premise and make a show which would hopefully change attitudes towards television science fiction. Although it was a child of its cultural and sociological predecessors Galactica strove to be more and for the most part succeeded.

Return to... |

|---|

There can be few people who, even if they haven’t seen it, won't be aware of Ronald Moore’s re-imagining of the, well remembered, quaint but flawed Battlestar Galactica (1978 - 1979). The original show, created by Glen L. Larson (Buck Rogers in the 25th Century (1979), Magnum, P.I. (1980), Knight Rider (1982)), was produced following on from the runaway success of Star Wars (1977) and was similar enough for Lucas and Fox to take out a lawsuit against Universal. The show would eventually fall into the ignominious debacle that was Galactic 1980, which arguably produced, in its ten episode run, only a single good episode The Return of Starbuck (1980), which itself was a steal from John Boorman’s Hell in the Pacific (1968), though importantly it did introduce the idea of humanoid Cylons in The Night the Cylons Landed.

There can be few people who, even if they haven’t seen it, won't be aware of Ronald Moore’s re-imagining of the, well remembered, quaint but flawed Battlestar Galactica (1978 - 1979). The original show, created by Glen L. Larson (Buck Rogers in the 25th Century (1979), Magnum, P.I. (1980), Knight Rider (1982)), was produced following on from the runaway success of Star Wars (1977) and was similar enough for Lucas and Fox to take out a lawsuit against Universal. The show would eventually fall into the ignominious debacle that was Galactic 1980, which arguably produced, in its ten episode run, only a single good episode The Return of Starbuck (1980), which itself was a steal from John Boorman’s Hell in the Pacific (1968), though importantly it did introduce the idea of humanoid Cylons in The Night the Cylons Landed. During the fifties and sixties film and televised science fiction had moved some way from the optimism of Flash Gordon (1936) and Buck Rogers (1939) to encompass the creeping paranoia of the post war years, although the idea that the enemy was amongst us was exploited in films like

During the fifties and sixties film and televised science fiction had moved some way from the optimism of Flash Gordon (1936) and Buck Rogers (1939) to encompass the creeping paranoia of the post war years, although the idea that the enemy was amongst us was exploited in films like  Part of the problem was that science fiction was seen as part of ‘popular’ culture, popular being used in its original sense, unlike its use today to signify something that is successful, that is of a cultural artefact that arose from the people, folk culture was often viewed this way. Such culture was viewed as inferior to elitist culture - fine art, opera, ballet and the serious novel - and therefore of less value.

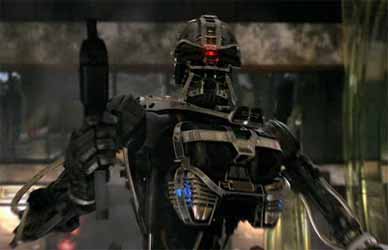

Part of the problem was that science fiction was seen as part of ‘popular’ culture, popular being used in its original sense, unlike its use today to signify something that is successful, that is of a cultural artefact that arose from the people, folk culture was often viewed this way. Such culture was viewed as inferior to elitist culture - fine art, opera, ballet and the serious novel - and therefore of less value. Both shows dealt with a human civilisation all but destroyed by the Cylons, a robotic race. In the original show the Cylons were all that were left of a reptilian race, who were at war with the humans. The reptiles created the robots to be their shock troops, the creators are only glimpsed in the person of the Imperious Leader, and Moore does have a little nod to this part of the show's mythos, in the Viper pilot’s jackets, the back of which is very reptilian, with its scale pattern motif.

Both shows dealt with a human civilisation all but destroyed by the Cylons, a robotic race. In the original show the Cylons were all that were left of a reptilian race, who were at war with the humans. The reptiles created the robots to be their shock troops, the creators are only glimpsed in the person of the Imperious Leader, and Moore does have a little nod to this part of the show's mythos, in the Viper pilot’s jackets, the back of which is very reptilian, with its scale pattern motif. For its time, the 1978 show was impressive, although prohibitively expensive because of the special effects, the best of which were provided by John Dykstra (Silent Running (1972), Star Wars (1977), Spider-Man (2002)), the Valley Forge, from

For its time, the 1978 show was impressive, although prohibitively expensive because of the special effects, the best of which were provided by John Dykstra (Silent Running (1972), Star Wars (1977), Spider-Man (2002)), the Valley Forge, from  There had been a number of attempts to resurrect the show in the years between Larson and Moore’s vision. Larson continued to pursue the idea of a movie and Richard Hatch (The original Captain Apollo) went so far as producing a half hour pilot sequel ‘The Second Coming’, the trailer did the rounds of conventions, garnering some good reviews, but unless you were lucky enough to be at one of these gatherings, you will never get a chance to make your own mind up as the whole thing was shelved indefinitely. However, all this hard work came to nothing when the studio went with the re-imagining. Although Richard Hatch was bitterly opposed to the project he eventually relented taking the role of Tom Zarek.

There had been a number of attempts to resurrect the show in the years between Larson and Moore’s vision. Larson continued to pursue the idea of a movie and Richard Hatch (The original Captain Apollo) went so far as producing a half hour pilot sequel ‘The Second Coming’, the trailer did the rounds of conventions, garnering some good reviews, but unless you were lucky enough to be at one of these gatherings, you will never get a chance to make your own mind up as the whole thing was shelved indefinitely. However, all this hard work came to nothing when the studio went with the re-imagining. Although Richard Hatch was bitterly opposed to the project he eventually relented taking the role of Tom Zarek.