|

Click here to return to the main site. Pete Travis (Director) - Vantage Point Pete Travis was born in Manchester, Great Britain. He's directed TV shows including The Bill and Cold Feet. He shot to fame after directing Omagh - a dramatisation based on the Omagh bombing which won a BAFTA for Best Single Drama. ReviewGraveyard caught up with Travis as Vantage Point, his first major movie, was due for release on DVD... ReviewGraveyard: Is this a film that really only came together fully in the edit?

RG: Was each viewpoint filmed individually? PT: Obviously you don’t just spend three weeks filming one story and three weeks filming another. What we did do, though, was spend four or five days on each character’s particular part of the story. For example, when the president walks into the plaza, you spend four days filming Dennis Quaid’s version of that and then William Hurt would walk into the plaza again and you’d film Forest Whitaker’s version of it. With the way the story’s told and the narrative style that’s developed by concentrating on the point of view of it, you’re trying to have the camera get under the skin of the characters, because I think part of it’s not just about what you see but what you feel and the things you see and the things you don’t see. The same when Forest goes in, it’s a very different story again. For him, it’s a bright, optimistic day and it’s full of life. It’s trying to get a difference to it every time. RG: Do you think it would have worked as a linear narrative? PT: It was never considered for me as a linear narrative. I think the star of the movie, in a strange way, is the way it reveals itself. I think what it’s about was always a point of view. It was about the way the truth is never quite as simple as you think it is. I don’t think you could have told that story in a linear way. RG: You managed to a assemble a pretty impressive cast - was that a case of securing one name and the rest followed?

And also I think the honest truth of it was that people saw Omagh and loved the acting in it and loved the realism of the performances there and wanted to be part of something that felt real and have the chance to act in a way that was kind of uninhibited, I think they were excited by the idea of that and the script. RG: Is it significant that as non-American you bring a different perspective to the material, especially as it deals with America’s position in the world and how the world perceives America? PT: I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the studio picked a European director to make this movie. I think they wanted a different kind of approach to it. I think it would have been a very different film if it had been directed by an American, because there is no one world view in this film, you don’t solve the mystery of what’s happened to the American president by only following the American characters, you have to follow the European characters and you have to get under the skin of the bad guys as well as the good guys and that’s a very bold thing for a big American movie to be doing. I kind of fell in love with movies like Three Days Of The Condor and The Parallax View; those were the movies that I wanted to make, at a time when American cinema was huge, successful movies with big stars but very, very smart movies - action movies at a time when action movies and intelligence went together, and that’s not always the case now. That was what was attractive to me about this film – it felt like it came from another era. I think that there is no black and white in this film and you’re forced to confront different sides of different people’s characters wherever they come from in the world. Not all the good guys are good and not all the bad guys are totally bad. It’s certainly one of the things that interested me about the film and I think that’s what makes it, in a funny kind of way, a peculiarly European take on an American story. It has a sophistication to it that I think it’s important. RG: The the audio commentary on the DVD you mentioned that you asked the Secret Service about the use of doubles and whether there was any truth in it...

Barry Levy, the writer, had a kind of mole guy in the Secret Service he would secretly phone up every now and again and he would always pretend to be somebody else. And we had the guy who trains the Secret Service who was our consultant on the project – he made sure that all the actors used the proper language; that they knew how to use the microphone and how to carry a gun properly, all the protocol of the way they work and operate. Particularly in terms of the way the plot reveals itself later on, it was important that that was realistic when the story turns, that what the Secret Service do there seems real and not unbelievable, it was important for us to get that right. RG: Did you have a consideration in making too clever and realistic a thriller on this subject that you’re suggesting ways it could be done?

RG: Did the Secret Service ever say: “This is too hot a subject, we’re not even going to discuss this aspect of the plot”? PT: We didn’t have a problem finding Secret Service guys that wanted to talk to us about what their work’s like. No, I think that people from that world want to see themselves portrayed in a way that’s true. Everybody went out of the way to make everything seem real, so William Hurt spent time talking to Bill Clinton about what it was like to be the president, Sigourney Weaver spent a lot of time with news journalists, Edgar Ramirez spent some time being trained by a Spanish security guy and all the [actors playing] Secret Service men went on a Secret Service boot camp. And even the designer when it comes to rebuilding Salamanca in Mexico, it’s literally a brick-for-brick replica, a 90-metre-square set that you could take someone from Salamanca and they wouldn’t know the difference. The realism of it was really important, because I think for me that’s part of the excitement of the story.

PT: I got lot’s of really interesting ideas about point-of-view, because when you meet those guys you realise that they really do see the world in a different way. One of the reasons we went for that kind of fast editing style when Denis is standing on the podium is that literally those guys could be standing there and hearing conversations in the crowd. They develop a kind of sense of what they want to look for and the way they are looking for certain kinds of things so that when Denis is looking at the guy who’s putting his hand in his pocket, that’s the kind of thing they see in a crowd; they go into a room and they automatically know where everybody is. It’s really quite eerie when you meet people like that but we got some really interesting ideas in terms of the way we could shoot a certain sequence from that, that there was a kind of in-built paranoia in the Secret Service because they’ve always got a kind of sixth sense about stuff, some of which can be totally over the top, for example, in our story Denis completely overreacts to an innocent man with a camera because he’s slightly paranoid, but I think that they definitely see the world in a different way. RG: How difficult was it to get the car chase right?

It was a lot of fun to shoot. We wanted obviously to make it feel real so it was pretty hairy to shoot because those spectators in the street really are as close to that car when it’s driving fast and that stunt when the Jaguar goes up in the air, that really did happen. There’s no CGI in the car chase - all of those gags, which is what the stunt men call them, really did happen. I think we were going for more putting the camera in the car, making it feel like you’re in it. That’s the thing you get from The French Connection, you feel like you’re in that chase. We weren’t as reckless as William Friedkin; we didn’t go and shoot it without anybody’s permission because you can’t do that now, even in Mexico. Everything’s planned out because everyone’s a bit more safety conscious now but you’re trying to get that level of realism and danger into it. RG: The biggest twist demands the biggest suspension of disbelief and it’s never satisfactorily explained. Is the audience supposed to just accept that?

I mean, the terrorists don’t have a cause that we’re aware of, they don’t belong to a group, we don’t really know what they’re trying to achieve. And in the same way, in terms of the twist in the movie, we’re trying to give enough to understand the nature of the person that it might be and why they’re doing what they’re doing but we’re kind of leaving that up to your imagination to figure out yourself. The individual motivation of each of the characters was less interesting than how they reacted in the moment, because this is what for me the film is about: how we deal with a crisis, how, when you think you’ve got it under control, it totally turns upside down and what are you going to do about it. So that was kind of why we purposely kept that vague. RG: Bruce McGill’s character is interesting...

I wanted a world in which the president was surrounded by people that wanted him to go one way or another and he’s kind of pushed into a situation by his own people that presents him with a huge moral dilemma. That’s what was interesting for me, what does he do when he gets into that position and can he really be a president and can you hide under a table when you’re the leader of the free world because you’re worried about getting shot. All of those things I think were really interesting things that you needed. You needed Bruce McGill’s bullishness to push him in a certain way. RG: Were the actors kept in the dark about plot points that were external to their immediate scenes? PT: No, that wasn’t really practical and it wasn’t really necessary. I think they were kept in the dark in terms of the cliffhangers in the story, because in the script everybody’s story began and ended at the same point, but in the cut of the film we made a very conscious decision that all the stories begin at the same point but where they all end is a little bit further than the one before, and they all end on a cliffhanger. What was exciting was that each of the actors got to play the truth of their story in a different way. For example, when you see Edgar Ramirez and Ayelet Zurer through Forest Whitaker’s eyes, they look like lovers and they’re holding hands and they look like they’re about to kiss each other. They obviously did the same actions but they played up that sense of it because that’s what Forest saw, and when they came to play that in their scene you could see that they hated the sight of each other and were about to throttle each other. It’s like one guy who’s missing his family and feeling a bit alone, you know when you’re wife’s left you it feels like the whole world is snogging and you’re all by yourself and everybody’s kissing except him, but he doesn’t see the truth of what’s there and I think that was what the actors brought extra to it. None of that was really in the script. RG: There have been comparisons with Rashomon - is that just lazy film journalism?

RG: Was the trailer a headache because you’ve got to decide how much you want revealed? PT: Yeah. Obviously the trailer’s about bums on seats and you want people to be intrigued to see the film, so the constant challenge is how much do you show, how much do you not show. I think we thought that by making it seem that there was something more going on than you thought was interesting. Some people I think get the twist in the trailer and some people don’t. I think it’s about everybody knows the movie’s about a presidential assassination; they’re going to know that before they come. I was intrigued by the idea that you could make them believe that there was a bit more, that the truth was slightly more complicated than that. RG: Thank you for your time.

Vantage Point is released on DVD and Blu-ray from Sony Pictures Home Entertainment from 04 August 2008. Click here to buy Vantage Point on DVD for £9.98 (RRP: £19.99) Click here to buy Vantage Point on Blu-ray for £17.98 (RRP: £24.99) Click here to buy Vantage Point on UMD for £8.30 (RRP: £12.99) Return to... |

|---|

Pete Travis: No, it comes together in the way you shoot it. It starts with a script - the other star of the movie is the structure and the way the story is told. The way it’s shot is what makes it compelling. Yeah, you make decisions in the edit that can keep it exciting and can give you cliffhangers to the story and help you shape it but the truth of the story is in the way it’s told and the way it’s put together and the people who are in it.

Pete Travis: No, it comes together in the way you shoot it. It starts with a script - the other star of the movie is the structure and the way the story is told. The way it’s shot is what makes it compelling. Yeah, you make decisions in the edit that can keep it exciting and can give you cliffhangers to the story and help you shape it but the truth of the story is in the way it’s told and the way it’s put together and the people who are in it. I really wanted to make it clear in terms of the way we shot it that the camera can kind of tell you something about a person, so that when Denis gets out of the car you see things that you don’t see in Sigourney’s story because you see the cameras flashing and you hear the sound that sounds like gunfire, the crowd are very hostile and when he goes into the plaza the sound is very different.

I really wanted to make it clear in terms of the way we shot it that the camera can kind of tell you something about a person, so that when Denis gets out of the car you see things that you don’t see in Sigourney’s story because you see the cameras flashing and you hear the sound that sounds like gunfire, the crowd are very hostile and when he goes into the plaza the sound is very different. PT: No, I think they were all attracted to two things, really: I think they all loved the script and the intelligence of it, and I think people like William and Sigourney and Forest don’t normally do big action movies and were excited by a film that was smart and was about something.

PT: No, I think they were all attracted to two things, really: I think they all loved the script and the intelligence of it, and I think people like William and Sigourney and Forest don’t normally do big action movies and were excited by a film that was smart and was about something. Normally in a movie like this, Denis Quaid would just save the day all by himself and the movie would be all about him. What was attractive to me was the fact that it wasn’t that, that it was kind of subtle, in a way a very European movie about a big event that was seen through different people’s eyes.

Normally in a movie like this, Denis Quaid would just save the day all by himself and the movie would be all about him. What was attractive to me was the fact that it wasn’t that, that it was kind of subtle, in a way a very European movie about a big event that was seen through different people’s eyes. PT: I asked the Secret Service: “Does the president have a double or does he not?” and they wouldn’t deny it or say he didn’t, but they certainly didn’t say he did. There have been rumours that Reagan did sometimes have somebody that would sit in a car. And who knows? I can believe it could happen but did anybody tell us it did or didn’t happen? No, they didn’t.

PT: I asked the Secret Service: “Does the president have a double or does he not?” and they wouldn’t deny it or say he didn’t, but they certainly didn’t say he did. There have been rumours that Reagan did sometimes have somebody that would sit in a car. And who knows? I can believe it could happen but did anybody tell us it did or didn’t happen? No, they didn’t. PT: I think this is a fiction and real life is never as simple as that and hopefully people will see the movie as a piece of smart entertainment and that’s what it exists as. We’re dealing with real things but it’s fiction and I want people to enjoy the movie and be entertained by it, not take ridiculous ideas from it about what they should do in their real life.

PT: I think this is a fiction and real life is never as simple as that and hopefully people will see the movie as a piece of smart entertainment and that’s what it exists as. We’re dealing with real things but it’s fiction and I want people to enjoy the movie and be entertained by it, not take ridiculous ideas from it about what they should do in their real life.

PT: It sounds ridiculous but the car chase was kind of easy. The action in the movie is some of the easier stuff to shoot because it’s exciting. You basically sit and watch your favourite car chase, so you sit and watch The French Connection and study it shot-by-shot and go “I want to do that but better or bigger or in half the amount of time”. And then you literally sit down with model cars backing into each other and plan all the stunts. It’s ridiculously childish - it’s like boys with toys.

PT: It sounds ridiculous but the car chase was kind of easy. The action in the movie is some of the easier stuff to shoot because it’s exciting. You basically sit and watch your favourite car chase, so you sit and watch The French Connection and study it shot-by-shot and go “I want to do that but better or bigger or in half the amount of time”. And then you literally sit down with model cars backing into each other and plan all the stunts. It’s ridiculously childish - it’s like boys with toys.

PT: Well, I love Bruce McGill, he’s one of my favourite actors of all time and I’m glad I managed to persuade him to be in it, I’ve just loved everything he’s done. He’s the hawk clearly, he’s the scary man, and he loved playing the scary man and I loved him doing it. And he was a great counterpoint to William’s president.

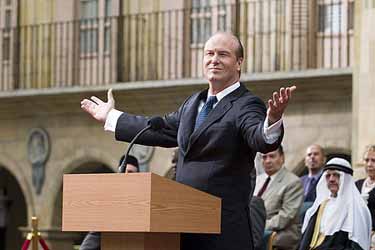

PT: Well, I love Bruce McGill, he’s one of my favourite actors of all time and I’m glad I managed to persuade him to be in it, I’ve just loved everything he’s done. He’s the hawk clearly, he’s the scary man, and he loved playing the scary man and I loved him doing it. And he was a great counterpoint to William’s president. So the final cut of the movie is slightly different to the script in that respect. But it felt like, in a way you’ve got such big actors involved in the story it’s almost impossible to keep those secrets from everyone. But one of the things that was very exciting for me that wasn’t in the script that all the actors brought to it, and you particularly noticed it with William Hurt’s performance, was that we thought we knew president, that when he comes into the plaza and opens his arms and gets shot and falls over it was the happy, smiling man that shook everybody’s hand, and then you meet this other man who’s totally different and literally the whole crew were totally shocked, and I don’t think even I was expecting him to be such a different kind of a guy.

So the final cut of the movie is slightly different to the script in that respect. But it felt like, in a way you’ve got such big actors involved in the story it’s almost impossible to keep those secrets from everyone. But one of the things that was very exciting for me that wasn’t in the script that all the actors brought to it, and you particularly noticed it with William Hurt’s performance, was that we thought we knew president, that when he comes into the plaza and opens his arms and gets shot and falls over it was the happy, smiling man that shook everybody’s hand, and then you meet this other man who’s totally different and literally the whole crew were totally shocked, and I don’t think even I was expecting him to be such a different kind of a guy. PT: I would be deeply flattered to have that movie mentioned even in the same breath as our film - it’s one of the best movies of all time directed by one of the best directors ever. I mean, we were inspired by it, clearly - how could you not be? But we’re taking the ideas of that, of the ways of seeing the world, the way the truth is not as simple as you think it is and trying to make it work for now. But I wouldn’t dream of comparing our movie to that - it’s one of the greatest movies of all time.

PT: I would be deeply flattered to have that movie mentioned even in the same breath as our film - it’s one of the best movies of all time directed by one of the best directors ever. I mean, we were inspired by it, clearly - how could you not be? But we’re taking the ideas of that, of the ways of seeing the world, the way the truth is not as simple as you think it is and trying to make it work for now. But I wouldn’t dream of comparing our movie to that - it’s one of the greatest movies of all time.