|

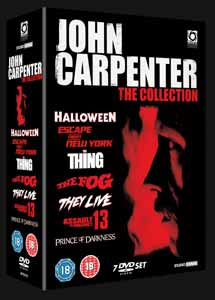

Click here to return to the main site. John Carpenter (Director) John Carpenter was born on 16 January 1948, in New York and began making short films in 1962. He won an academy award for Best Live-Action Short Subject in 1970, for The Resurrection of Broncho Billy (1970). Shortly afterwards he started work on Dark Star. Since then he's gone on to create some of the industry's best sci-fi and horror movies including Halloween, Escape from New York, The Fog and Assault on Precinct 13. Reviewgraveyard.com chatted with Carpenter as The John Carpenter Collection box set was released on DVD... ReviewGraveyard: Tell us about your experiences of your first feature movie, Dark Star.

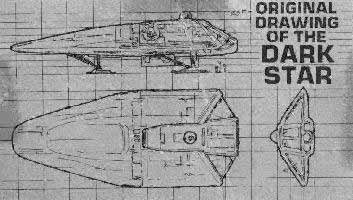

We put the movie together on 16mm over the course of four years... three or four years. It wasn’t a movie shoot like we think of today, it wasn’t ‘you shoot the whole movie in one section in one block of time’, it was ‘shoot a scene, raise money, shoot a scene months later, raise money, shoot a scene’... The effects were basically just a lot of animated effects, of on-set effects, kind of old-fashioned, old-school stuff, and it was a ridiculously ambitious movie for what we were doing I look at it now, pieces of it - I don’t like to look at the whole thing anymore, it’s an amateur film. It was kind of a nice little amateur movie made at the time... Dan O’ Bannon really designed the effects of the movie so I have to give him ultimate credit for that and, uh, the ship itself, the dark star - the ship, was sculpted by model maker Greg Jean, and that was fibreglass. But the bomb, for instance, was a model of a box car - I believe - or a train, a truck or a railroad car. Since 2001 it's model kit’s stuck on, that’s the standard, state of the art, makes it look sort of believable, as a scientific possibility. So we did the same thing...

My first film was released in theatres which was just fabulous, at least on my birthday, 16 January 1975. I was hoping, praying, that someone would come and say: "We want you to direct a movie" because that’s what I’ve always wanted... and nobody came - it didn’t happen. but I did get an agent out of the situation, and I began writing screenplays to get myself into the business. But it was a first step, it was something to show. I don’t think it would impress too many people...

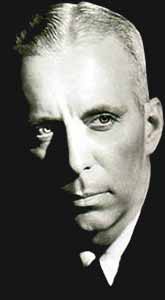

If you look at the movie there’s some exterior shooting but mostly it takes place in one set, well that was the, you know... that was the gig at the time and also that was my first Panavision widescreen film which I was dying to do, because I love widescreen. The most explicit tribute to Howard Hawks was in the credits of Assault on Precinct 13, the editor was John T. Chance, that’s the character, the sheriff’s character from Rio Bravo, that’s... if anyone wants to see it. But, just the idea of people in an enclosed space, dealing with this kind of hostile world outside, that was sort of Hawks’, you look at the Dawn Patrol, there’s this little bar, where the flyers would find meaning, you look at Only Angels Have Wings it’s the same thing, everything is dangerous out in the outside world, but here is where you have some sort of safety - Rio Bravo, El Dorado, I mean all the action kind of films, even Air force - the safety is in the airplane, in a sense, all around is this kind of evil, and that’s always appealed to me.

All throughout his movies, regardless of how studio-driven they were, they were his personal canvas to work on. That I admire a great deal, and also his invisible camera technique which was, in a sense, the technique of the thirties and forties when sound came in. The invisible technique was that you didn’t notice the camera in there, it was just in the right place, I always admired that. I think its deceptively simple - it’s hard to get that and to pull that off... RG: Tell us about how you cleverly avoided an MPAA X Rating on Assault on Precinct 13... JC: I don’t know how clever it was. We had a scene where a little girl gets killed with a gun, and it was pretty horrible at the time - explicit. I don’t think I’d do it again but I was young and stupid. So there it is on the screen and the MPAA said they were going to give us an X, so the distributor of the movie suggested: "Just cut it out. We’ll show it to the MPAA and then just let it go as it was” and those were the old days where they didn’t check so much, so that’s what we did... So I don’t know, I don’t really think it was very clever, it was pretty ham-fisted... RG: Tell us about your views on composing for your movies.

If you think in rock ‘n roll the most famous riff-driven band is the Rolling Stones, I can say ‘Satisfaction’ to you and you’d know the riff of it, well that’s what I employ... not as successfully but I use it. On Assault I had two or three days to do the soundtrack, so I was on a synthesizer, and a piano. In that case you don’t score the film, what you do is you record three or four or five pieces of music that you can use in various places and that’s what I did in that case - very quick, very fast, very simple. I’ve always been inspired by Bernard Herman who was a composer - who was, I think, probably the best - who had this incredible impact, using very simple means. The best example of that being Psycho as a score with strings only. His idea was more like a knife, or razor edge, and then the scene in the shower with the kind of attacking string section. But his work is just amazing... I remember in Christine I did a particular piece of music for a scene and they said to me: "We can use this under the whole movie, this supports the mood, and it’s just there invisibly." So it was a little like Hawks’ invisible camera style - music is kind of invisible. Now there’s another style of musical composition, kind of Max Steiner-esque - he’s the king of Mickey Mouse; which is that in Mickey Mousing you emphasize every movement on the screen. There's a perfect example of Mickey Mousing in King Kong - that BOOM! BOOM! BOOM! - every move is hit with music, and that’s also great. The king of Mickey Mousing, I would say, is probably John Williams... RG: You shot Halloween, once again on a very low budget, three hundred thousand dollars, very quickly on a twenty one day schedule. Is that creatively invigorating to be under that kind of pressure?

What it is, it’s focusing, like going into war, it focuses you on, as a director, saying: "Okay, I’m not going to be able to get this material... this script done the way I might prefer it, so let me approach this in a different way. How much can I get done in a single shot - in a wide shot - that can carry me along, so I’m not relying on a lot of setups. So it focuses your attention, and you just have to go for the essence of the scene, it’s very good for a director to have to do that... I wouldn’t say it’s fun or pleasant. It’s always nice to have enough time and money to do it. Always nice... You do a low-budget film and you don’t have a lot of choices. For the mask for Michael Myers, we couldn’t manufacture our own, so our production designer, Tommy Lee Wallace, went up to Burt Wheeler’s magic shop on Hollywood Blvd and he bought two masks. One was a clown mask, so he wears a clown mask, and I suppose there’s a certain iconic image to that. But the other choice... He bought a William Shatner mask which doesn’t look anything like William Shatner. But it’s a human face, with some fake hair on it and he spray-painted it - kind of paled it down - and changed the hair a little bit, changed the eye holes. That was more like what was written in the script, the script was written to say: "The pale features of a human face" - it’s a face mask, is what it was meant to be. So that’s the one that was the most effective - it was as simple as that... Having a lot of time and money creates its own problems, but it’s not necessarily a bad thing to have too much of anything. I don’t think any director’s going to tell you: "Oh my god! I have too much time on this film... That’s awful. Can’t we just cut some days out of this, can we cut the budget down? This is just terrible!" No, it was better but there are other pressures that go with that, that you trade off. Yes you can take your time, you can shoot a film in the way you think is the best way to do it, but on the other hand it kills your momentum in terms of... There’s something about the momentum in a film. If you can get the cast and crew going at a speed that shows up on screen. And that’s a problem you’ve got to watch out for that in bigger budget movies.

The movie came out to these dreadful reviews. It was platformed across the country, moved from region to region. So it would open in Los Angeles and then play in San Diego and then it would play in Phoenix and then slowly but surely the prints, and there weren’t many of them, would move across the country. By the time it got to the East Coast I’ll bet those prints were in pretty bad shape. It was a drive-in film, it was an exploitation horror film, but we got a good review in The Village Voice, kind of re-reviewed by people and it started, word of mouth started building on that movie and it began to make some bucks and I noticed it because people started paying attention to me. People began making offers to me to direct films, and that was the surest sign that it had become successful. Today I look back on it as just absolutely wonderful, it’s real lucky we were just trying to make a movie, hopefully, you know it was going to be something special but I can’t say I knew that... My involvement with Rob Zombie’s remake was to extend my hand and have a cheque placed in it, and then close my hand and return to my position on the couch watching basketball. RG: What do you think with what he did with it?

RG: On The Fog you got to work with Janet Leigh. What was that like? JC: Janet Leigh was fabulous, she’s a real studio trained actress, back from the old days. One of the things that really impressed me was… we had a scene shot in a restaurant there in Point Reyes, California, and she had to break down and cry. For technical reasons, because it was a very long sequence, she had to do it over and over and over again. Boy, she could do it every time, just: Bang! Bang! Bang! That’s that old studio training, you know, she didn’t have to sum it up - the emotion - she knew how to do it and, a very wonderful lady... RG: One of the influences on the film is an obscure British movie called The Trollenberg Terror. How did you discover that? JC: I love that movie. In America I know that movie by its re-title The Crawling Eye. The Crawling Eye was a movie I saw in 1958 when I was a kid - mainly the fog moving, that’s the inspiration for it, we didn’t have the big eyeballs crawling in the fog. RG: And you also said a visit to Stonehenge was a big influence on The Fog... JC: Just a visual, the fog moving across, standing in the plain there looking at Stonehenge and thinking: "This is smaller than I thought it would be." I thought it would be bigger, but it’s still impressive looking across the plain there - there’s the fog. The fog - what’s going on there, looks like a ghost story type thing, so that’s what it was...

I made it science fictional and I kind of thought of Clint Eastwood as the character would be playing it. It’s also inspired roughly from a science fiction novel called either Planet of the Damned or Planet of No Return, I can’t remember which, but the idea is this most dangerous planet in the galaxy and someone has to be sent in there. Who do you get? The most dangerous man in the galaxy is who you get to go in, so that was the essential idea... There’s a big idea prison movie in the sense that New York is a prison - is the first thing you have to swallow, and the second thing you have to swallow is the president of the United States crashes in there. The third thing is that this eye patched guy goes in to rescue him... and the rest is a sort of series of adventures. RG: James Cameron worked on that movie in the special effects department. Do you remember him from back then?

Kurt and I met on Elvis, he played Elvis Presley - that was the three hour movie I did for television - and he was just terrific. He’s an all-timer, in the sense that he was a child actor. His discipline is beyond reproach - he comes ready to go, he knows the job, the movie making job, and he’s just enormously talented. So we became friends... RG: Escape From New York, like a lot of your early films portrays a very post-apocalyptic future world. Are you surprised that mankind has made it this far? JC: Actually yes, after the, err, Cuban Missile Crisis - which I lived through knowing what was going on. After that whole confrontation, the possibility of nuclear holocaust, everything is amazing to me now. I’m a long term optimist but a short term pessimist, you know. I think it’s all f*cked in the short term but in the long term it may work out...

Hawks’ film, well The Thing From Another World, that Christian Nyby directed, supposedly, was very much of its time in the fifties, very early fifties. It came from a short story called Who Goes There, actually a novella, so we went back to the novella. This whole imitative business was never covered in Hawks’ movie, so we just struck out on our own. This was the early eighties, ’82, so I made it very dark but, somewhat… I thought at the time, realistic, as opposed to a… Hawks’ film which was very idealized. The Thing,The Prince of Darkness and In the Mouth of Madness are essentially about the end of the world in one way or the other; in a fanciful way. At the end of the world there’s no hope, you know, it’s gone, it’s over. And those films suggest in their own individual ways; it’s all over, it’s done, you know, it’s time to whip her... It seemed to me that They Live needed a kind of working guy, non middle class, blue-collar guy who’s a working poor, who are real and who are still real in this country so, uh, I thought Roddy Piper had a quality about him and not the personality you see in the wrestling ring or in his interviews. He did a great job for me... RG: And did he really come up with the line himself: "I’m here to kick ass and chew bubblegum, but I’m all out of bubblegum"?

RG: Do you think the film still has some relevant social commentary? JC: That’s never in it, that’s still with us - They Live is a documentary about what’s going on now... relevance, of course. Yeah it’s still here. Here’s my philosophy on it, I’ll just tell you - Ronald Reagan along with your gal there, Iron Lady Thatcher came into power my saying government was a problem. That’s an absolute lie - good government is a solution, bad government is a problem, not government, that’s all it is... RG: What are your feelings on movie violence? JC: That’s a tough one, you know… uh, because I defend the director’s right to show almost anything, I think we all have to use our… err, we have to use what’s inside of us to be the judge of what’s too much. On the other hand there are things that I think go too far... child pornography, I think, goes too far. RG: How do you feel about the latest vogue in horror cinema? JC: I bet you’re gonna say the words "torture porn" aren’t you? I bet you’re gonna say that, and now you didn’t say it, ok… everybody says that… Horror movies always indicate something in the culture in which they’re made and I think if you just think a minute about the plots of a lot of these films, you have Americans going to another country, and are being tortured... now if you think about our world, how does that fit in to what we know now? RG: Thank you for your time.

John Carpenter: The Collection is released on DVD from Optimum Home Entertainment from 06 October 2008. Click here to buy this DVD box set for £39.98 (RRP: £54.99) Return to... |

|---|

John Carpenter: Dark Star began as a student film when I was at the university of Southern California in 1970 and I was partnered with Dan O’ Bannon who is the production designer, editor and one of the actors in the film. He went on to have a very successful career as a writer and has directed on his own.

John Carpenter: Dark Star began as a student film when I was at the university of Southern California in 1970 and I was partnered with Dan O’ Bannon who is the production designer, editor and one of the actors in the film. He went on to have a very successful career as a writer and has directed on his own. All these movies, Dark Star included, were spawned... influenced by

All these movies, Dark Star included, were spawned... influenced by  Assault on Precinct 13 was one of two ideas that I came up with for this investor. He wouldn’t invest in a certain sum of money, we’d make the movie independently, and I just sat down and wrote it. The basic influence of Assault was Rio Bravo - the situation, but only really in a kind of generalized way, not in a specific way. But it was written to be an exploitation movie at the time, an action film, a siege film. I’m sitting here and it’s been... thirty-odd years since I made that film.

Assault on Precinct 13 was one of two ideas that I came up with for this investor. He wouldn’t invest in a certain sum of money, we’d make the movie independently, and I just sat down and wrote it. The basic influence of Assault was Rio Bravo - the situation, but only really in a kind of generalized way, not in a specific way. But it was written to be an exploitation movie at the time, an action film, a siege film. I’m sitting here and it’s been... thirty-odd years since I made that film. This is my own personal opinion, I think Howard Hawks [pictured] is maybe one of the greatest filmmakers because he’s made a great movie in every genre, and understands movies. He made films with movie stars, and there were popular films that also expressed his… personal point of view, his personal feelings about something; his feelings about masculinity, about male and female relationships, in comedy...

This is my own personal opinion, I think Howard Hawks [pictured] is maybe one of the greatest filmmakers because he’s made a great movie in every genre, and understands movies. He made films with movie stars, and there were popular films that also expressed his… personal point of view, his personal feelings about something; his feelings about masculinity, about male and female relationships, in comedy... JC: Well the one thing I have to say about me as a composer from my point of view is I’m cheap and I’m fast and I’m riff-driven - meaning that most of the title themes in my films, or most of the music, is driven by a riff.

JC: Well the one thing I have to say about me as a composer from my point of view is I’m cheap and I’m fast and I’m riff-driven - meaning that most of the title themes in my films, or most of the music, is driven by a riff. JC: You know it’s a great fantasy to say that - that having a low budget frees you. Actually it's terrifying because you’re never sure whether you’re going to make it and get all the work done. You’re operating under this enormous fear and pressure, and it’s not freeing.

JC: You know it’s a great fantasy to say that - that having a low budget frees you. Actually it's terrifying because you’re never sure whether you’re going to make it and get all the work done. You’re operating under this enormous fear and pressure, and it’s not freeing. Halloween came along and I had in mind the girl who was in Jaws 2, I can’t remember her name now... very talented actress and she didn’t want anything to do with it. There were a lot of people I wanted to be in Halloween. I wanted Christopher Lee or Peter Cushing to play in it and they didn’t want to do it. So Deborah Hill, my partner at the time, the producer, suggested Jamie Lee Curtis. She was on a contract at Universal on a TV show called… uh, can’t remember the name of it now, Alzheimer’s has set it. She was young, she was nineteen years old, a young actress and Deborah suggested it as an echo of Psycho. So Jamie came in and read and she was absolutely delightful and perfect for the part...

Halloween came along and I had in mind the girl who was in Jaws 2, I can’t remember her name now... very talented actress and she didn’t want anything to do with it. There were a lot of people I wanted to be in Halloween. I wanted Christopher Lee or Peter Cushing to play in it and they didn’t want to do it. So Deborah Hill, my partner at the time, the producer, suggested Jamie Lee Curtis. She was on a contract at Universal on a TV show called… uh, can’t remember the name of it now, Alzheimer’s has set it. She was young, she was nineteen years old, a young actress and Deborah suggested it as an echo of Psycho. So Jamie came in and read and she was absolutely delightful and perfect for the part... JC: I haven’t seen it. I have no comment. I don’t know what to say. But I will say this, Rob [pictured] is a friend of mine. He’s been a friend since ’96. He did some music for me on a film I made, so... I’m not going to say anything about his version. It’s his and I’m not going to critique it

JC: I haven’t seen it. I have no comment. I don’t know what to say. But I will say this, Rob [pictured] is a friend of mine. He’s been a friend since ’96. He did some music for me on a film I made, so... I’m not going to say anything about his version. It’s his and I’m not going to critique it Escape From New York was written in the seventies, and it was probably influenced a lot by Death Wish, the movie with Charles Bronson about a vigilante in New York killing - getting revenge for what happened to his family, that kind of thing. And that was...

Escape From New York was written in the seventies, and it was probably influenced a lot by Death Wish, the movie with Charles Bronson about a vigilante in New York killing - getting revenge for what happened to his family, that kind of thing. And that was...  JC: When I went over to visit the Corman facility, where the special effects were done, he was the genius, the resonant genius - everyone was talking about how great he was. I remember meeting him on the set, actually it was over in the San Fernando Valley, he was doing a glass painting for us. He was sitting on a hillside with some glass setup painting a New York skyline to be able to shoot the next shot. It was just beautiful – he was really technically great. So I said hi to him, we talked a little bit and that was about it...

JC: When I went over to visit the Corman facility, where the special effects were done, he was the genius, the resonant genius - everyone was talking about how great he was. I remember meeting him on the set, actually it was over in the San Fernando Valley, he was doing a glass painting for us. He was sitting on a hillside with some glass setup painting a New York skyline to be able to shoot the next shot. It was just beautiful – he was really technically great. So I said hi to him, we talked a little bit and that was about it... The Thing was a movie that was an assignment, that’s the first movie that we’ve talked about that I did not write. This was my first studio feature and, uh, it had nothing to do with the Hawks movie, that’s one of the things that… immediately from the beginning I decided not to even get near.

The Thing was a movie that was an assignment, that’s the first movie that we’ve talked about that I did not write. This was my first studio feature and, uh, it had nothing to do with the Hawks movie, that’s one of the things that… immediately from the beginning I decided not to even get near. JC: When we started working on the film together he gave me several sheets of paper and he said: " These are things that I have said; that I made up for my wrestling interviews. They’re lines that I’ve used. If I’m gonna do an interview, about some wrestler I’m gonna meet on Saturday night, I’ll say these lines". Some of them were not what I needed for the film but that particular one I thought: "That’s pretty great - and we can use this, it’s way out of context here in a way but it’s fun." So yes, it’s his, so he wrote it.

JC: When we started working on the film together he gave me several sheets of paper and he said: " These are things that I have said; that I made up for my wrestling interviews. They’re lines that I’ve used. If I’m gonna do an interview, about some wrestler I’m gonna meet on Saturday night, I’ll say these lines". Some of them were not what I needed for the film but that particular one I thought: "That’s pretty great - and we can use this, it’s way out of context here in a way but it’s fun." So yes, it’s his, so he wrote it. But there’s a part of me that says: "Yeah I can see, coz if you fake it I can understand", and there’s another part of me… that’s the dichotomy, in the sense the battle with an artist if you approach… if you approach a piece of material that has some real violence in it, you know… uh, you have to figure out how to do it.

But there’s a part of me that says: "Yeah I can see, coz if you fake it I can understand", and there’s another part of me… that’s the dichotomy, in the sense the battle with an artist if you approach… if you approach a piece of material that has some real violence in it, you know… uh, you have to figure out how to do it.