|

Click here to return to the main site. DVD Review

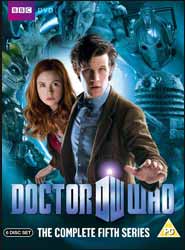

WARNING: CONTAINS SPOILERS! This box set contains all thirteen episodes of Matt Smith’s first season as the Doctor, which is also Steven Moffat’s first season as showrunner. Previously released on single discs containing three or four episodes apiece, the shows this time are accompanied by additional special features. The Doctor has regenerated into a brand-new man, but danger strikes before he can even recover. With the TARDIS wrecked and the sonic screwdriver destroyed, the new Doctor has just 20 minutes to save the world, and only Amy Pond to help him... In The Eleventh Hour, the new Doctor emerges from the TARDIS like a newborn, wet (from the swimming pool, which is in the library) and unsteady on his feet. He is also a fussy eater, because he has a new mouth with new taste buds. These early eccentricities certainly made me laugh and endeared me to him, though I am a little concerned that younger viewers might copy his antics and cause their parents grief by believing it’s cool to spit out their food! Gradually, as the after-effects of his regeneration subside, the Eleventh Doctor’s personality settles into a unique blend of new and old Who, with instances of Tennant-style chattiness, surprise and anger combined with quieter Troughton- and Davisonesque moments. No newly regenerated Doctor has ever been so active before. A new Doctor often spends much of his first adventure physically or mentally incapacitated. Even the Second Doctor had a bit of a lie down at the beginning of The Power of the Daleks. However, the Eleventh Doctor is forced to solve problems straight away, starting with the mysterious crack in the bedroom wall of little Amelia Pond (the brilliant Caitlin Blackwood). To my mind, the best part of this episode is the first 16 minutes, during which the action centres on Amelia’s creepy house during the night. The plot loses some of its focus, and some of my attention, when it widens its scope to encompass the village of Leadworth. This is not to discredit Karen Gillan, who dominates the screen when she appears as the grown-up Amy during the final 45 minutes of the show. She combines the bolshiness and wide-eyed wonder that are essential to the role of the modern companion with an eccentricity all of her own. Amy has a greater sense of self-importance than most or all previous companions - she is the centre of her universe, rather than a satellite of the Doctor. Gillan is sexy too - and not just when she’s wearing her kinky kissogram policewoman outfit. In fact, she has been accused of being too sexy for Doctor Who. Evidently the critics voicing such opinions have overlooked the miniskirts and other skimpy outfits worn in past decades by Zoe, Liz, Jo, Leela, Tegan and Peri. However, there is a new element of physical desire in Amy’s attitude to the Doctor, which is evident here when she lustfully observes the Time Lord getting undressed. Though eyebrow-raising, this is arguably more realistic than the chaste adoration of Rose and Martha. A characteristic of Moffat’s Who writing is his propensity to adapt, revise and revisit (one might, less charitably, say rehash) old ideas, especially his own, and this episode is no exception. As in Moffat’s The Girl in the Fireplace, the Doctor encounters a little girl, then leaves her, seemingly for just a few minutes, only to find that years have passed by for her. As in The Christmas Invasion, the new Doctor makes a chaotic landing, breathes out golden post-regenerative breath (though this is understandable on the grounds of continuity), doesn’t don his new outfit until the end of the episode, and scares the aliens into retreat. As in another post-regeneration story, Spearhead From Space, the Doctor steals his clothes from a hospital. However, unlike Spearhead, he does not become a patient himself - as I was momentarily fooled into thinking when the action cuts from the Doctor being knocked unconscious to an ambulance arriving at the hospital. The version released in this box set thankfully reinstates the correct opening “sting” and the lightning effects that were missing from the opening titles on the single-disc release. However, there are still no “next time” trailers on any of the episodes, possibly because of a decision taken by the new production team. Presumably the theory is that while “next time” trailers have an important role to play in broadcast episodes, they are not an integral part of the enjoyment of a commercial release. I disagree, and I am extremely disappointed that these mini-masterpieces (especially the one for Victory of the Daleks) are not even included among the special features. The BBC logo at the start of each episode is also more intrusive than the logo used on the transmitted episodes. Aside from my annoyance at these deviations from the broadcast version, The Eleventh Hour is a strong start for the new series, Doctor, companion and production team. 8

The Doctor takes Amy on her first trip aboard the TARDIS to the distant future. Starship UK houses the future of the British people, as they search the stars for a new home. But as Amy explores the vessel, she encounters the terrifying Smilers... Following the wit, intrigue and excitement of The Eleventh Hour, The Beast Below is something of a disappointment. There are lots of good ideas here, too many ideas in fact, but they don’t all hang together. The survivors of an entire country escaping a devastated Earth in a spaceship - good idea (and a nice nod to The Ark in Space). Sinister painted mannequins in booths, whose smiling faces give way to angry frowns and then demonic grimaces when citizens fail to obey strict laws - good idea. A voting system that offers a choice between death and amnesia - good idea (and great satire: “once every five years, everyone chooses to forget what they’ve learned. Democracy in action”). A gun-toting, Cockney-accented, future monarch - good idea (and well played by Sophie Okonedo: “I’m the bloody queen, mate. Basically, I rule”). A giant space whale - good idea (and also the subject of Big Finish’s The Song of Megaptera). However, all these elements don’t really mesh into a coherent narrative. It’s as though the episode was cobbled together from leftover ideas that Moffat couldn’t work into other instalments. The plot invites a number of unanswered questions. Why does Starship UK favour design styles from the 20th century: red telephone boxes, London Underground signage, old BBC lettering? (Answer: because it’s easier to realise within the budget than something futuristic - once again in new Who, the future is retro.) Why was the UK left behind when all the other nations departed the planet? (My guess is that the UK, a country with a history of separatism, was initially sceptical about the threat of the solar flares and didn’t want to buy into the project with the other nations.) If the UK had the time and resources to capture a star-whale and build a massive spaceship around it, why it couldn’t make an engine, as the other countries appear to have done? (Maybe the Earth’s resources of certain essential materials had by then been exhausted.) The Beast Below redeems itself with its ending, though, in which Amy saves the day by making a beautiful observation about the Doctor and the star-whale, thus proving her worth as a companion. Then, of course, we see another crack in the universe... What a shame that the excellent “next time” trailer for Victory of the Daleks, which had been the icing on the cake on the broadcast version, is missing. When I first watched The Beast Below, I was disappointed. Viewed again in the context of surrounding episodes, it can be regarded more favourably, as a typically lightweight but inoffensive early-in-the-season episode, whose foreshadowing of things to come (more amnesia) initially went unnoticed. 5

The Doctor is called to London during World War II by an old friend, Winston Churchill. To the Time Lord’s horror, he finds the Daleks posing as a man-made secret weapon that Churchill calls “Ironsides” and hopes will win him the war... I really wanted to give Victory of the Daleks a higher mark, because it gets off to a great start. The first quarter of an hour is excellent, practically a retelling of Troughton’s missing debut story, The Power of the Daleks, transplanted to a Second World War setting. The Daleks, at their most devious, are once again pretending to be robot servants, and Winston Churchill (Ian McNeice) is all too eager to accept them if they can defeat the Nazis. Instead of “I am your servant”, the first Dalek we encounter tells the Doctor, “I am your soldier.” As in The Power of the Daleks, the Doctor knows what these creatures are, but no one will believe him. As in The Power of the Daleks, the Daleks recognise him, despite his recent regeneration: “Now, you know who I am. You always know.” Appropriately enough, the Eleventh Doctor is at his most Troughtonesque in this episode, in terms of both Smith’s performance and Mark Gatiss’s writing. Watch Smith’s body language as he confronts a Dalek for the first time, and later as he storms past one of them, giving it an affronted glare. The Doctor’s line, “What does hate look like, Amy? ... It looks like a Dalek, and I’m going to prove it,” is pure Troughton. Later on, he threatens the Daleks with “The final end”, a line delivered by the Second Doctor in The Evil of the Daleks. Unfortunately, following “Power of the Daleks in 15 minutes”, the plot veers off in a less interesting direction. I could have done with more intrigue with sneaky Daleks in the Cabinet War Rooms during the first half of the episode and fewer drawn-out, anti-climactic scenes with Bracewell (Bill Paterson) towards the end. The writer doesn’t delve too deeply into Churchill’s darker side, though he does show hints of it in the lengths to which the man would go to win the war. Churchill’s line, “If Hitler invaded Hell I would give the Devil himself a favourable reference,” paraphrases an actual statement attributed to him: “If Hitler invaded Hell I would make at least a favourable reference to the Devil in the House of Commons.” The new production team resists the temptation to continue the recent celebrity historical tradition of having the companion imitate the speech patterns of the time or attempt to coax a famous quotation from a renowned historical figure. I had fully expected Amy to try and get Churchill to discuss fighting on the beaches, and for the Doctor to tell her, “No, no, don’t... don’t do that...” but it was not to be. However, they couldn’t resist a sly reference to the Churchill car insurance ads, when Amy shouts, “Oi, Churchill!” I could have done without the redesigned Daleks, though I accept some of the reasons for changing them (which are revealed in the in-vision commentary and the behind-the-scenes featurette, The Daleks - Monster Files, also included in this box set). The new look aims to recapture the nostalgic appeal of the colourful Daleks seen in the 1960s in the TV21 comic strips and the Peter Cushing movies. Though personally I prefer the previous redesign, the sleek new models arguably remain truer to the intentions of the Daleks’ original designer, Raymond Cusick. Though the 2005 production team had retained the basic proportions of his design, they added lots of bolts and rivets, giving it a tough, armoured look. However, when Cusick visited the new series studios and production offices (as seen in the special feature Cusick in Cardiff, in The Space Museum / The Chase box set), he expressed his belief that the design should not show any such methods of construction, because bolts and rivets are products of human technology, whereas Dalek technology is far more advanced. While I don’t exactly love the new Daleks, I’m getting used to them over time. Despite the anti-climactic nature of the Daleks’ victory, it does make a nice change from the previous production team’s trend of having the Daleks “destroyed utterly”, only to return the next time via some unlikely means. This way, the Daleks will always be around, as they were during much of the old series. It’s only a partial victory then, but this relaunch of the Daleks has its moments. 5

A crashed spaceship, a shattered temple and a terrifying climb through the maze of the dead - River Song is back in the Doctor’s life, and she’s brought more trouble than even he can handle. A Weeping Angel is loose, and the Doctor is recruited to track it down... One of the most remarkable things about the two-part The Time of Angels / Flesh and Stone is that it was the first story Matt Smith and Karen Gillan recorded for this series. You wouldn’t know it from their performances, as they both appear to fully inhabit their characters straight away. It probably helped that writer Steven Moffat gave them such marvellous dialogue to work with, such as the Doctor’s fumbled response to River Song’s observation about the search for a Weeping Angel in a temple full of statues being like trying to find a needle in haystack: “A needle that looks like hay. A hay-like needle... of death. A hay-like needle of death in a haystack of... statues. No, yours was fine.” And on DVD, of course, unlike the original UK transmission, there’s no annoying animated Graham Norton to spoil the dramatic final line of The Time of Angels! This two-part story is very much a showcase for the talents of the Series 5 cast and crew as a whole, and Moffat in particular. It’s excitement all the way, right from the James Bond-style reintroduction of River Song (Alex Kingston). Not ashamed to revisit the show’s past just one week after the return of the Daleks, he brings back not just one but two of his most popular creations: Dr Song and the Weeping Angels (hmmm, that sounds like a band). For the purposes of the plot, the nature of the Angels is altered slightly (as is touched upon in the commentary and the not very in-depth behind-the-scenes featurette, The Weeping Angels - Monster Files) from their previous appearance in Blink. Their reactions are slower this time around (which is explained as the result of years of starvation and inactivity) and now they kill rather than transport their victims back through time (which is attributed to the Angels in Blink being mere “scavengers”).In an unfortunate similarity to River’s previous adventure, Silence in the Library / Forest of the Dead, the Angels can now also steal the voices of their victims. That is my harshest criticism of this two-parter, though I accept its necessity, and it does allow for some powerful exchanges between the Doctor and his enemy, especially during the second episode... 9

In the ruins of Alfava Metraxis and the wreck of the Byzantium, the Weeping Angels are coming back to life. Everyone tells Amy, “Whatever you do, don’t blink,” but as she is about to discover, not blinking might just be the worst thing you can do... Flesh and Stone has an even greater abundance of classic lines than The Time of Angels. From the Doctor’s “We’ll all plunge to our deaths. See, I’ve thought about it,” to River Song’s “I absolutely trust him,” and the Doctor’s “It’s a thing in progress. Respect the thing,” the list just goes on. When I watched this episode again, some of the Eleventh Doctor’s fallibility reminded me of two of my favourite former Doctors, Davison and Troughton - though by this point I have largely ceased to regard Smith’s performance in terms of other actors who have played the role. To my mind, he is now very much his own Doctor. For instance, I cannot imagine any other incarnation reacting in the way that the Eleventh Doctor does to the difficult decisions he faces here. Similarly, no other companion has ever carried on like Amy does at the end of this episode! Seeing a companion behaving so overtly sexually towards the Doctor is a real shock to the system. For some viewers, it crossed a line in terms of what constitutes acceptable family viewing. For me, it was like getting an unexpected drunken snog from an attractive but hitherto chaste friend - it feels somehow wrong yet also irresistibly good! Moffat writes the scene well, taking a humorous approach (as you might expect from the writer of Coupling), having paved the way beforehand by having Amy lustfully observe the undressed Doctor in The Eleventh Hour, an incident that was also played for laughs. It’s probably no coincidence that the scene occurs in a River Song episode. It’s as though the writer is saying to us: “OK, so you’ve bought the idea that maybe the Doctor will have a wife in his future. Well, how about this...?” The episode also boasts a neat spin on the idea of not blinking when the Angels are nearby (here Amy cannot open her eyes for more than a few seconds or she will die), fresh questions about River just as we thought we’d figured her out, and a major advancement of the “cracks in the universe” story arc that I didn’t expect so early on in the season. It’s a show in progress. Respect the show. 9

The House of Calvierri has the whole of Venice under its protection, but something is very wrong. There are blood-drained corpses in the street, something lurks in the canal, and the Calvierri girls are the loveliest in town, except when you glance in the mirror... Following the sheer brilliance of the Weeping Angels two-parter, The Vampires of Venice is merely good. The production values are high, with Trogir in Croatia standing in convincingly for 16th-century Venice, plus some impressive CGI monsters. However, there is a nagging sense of having been here before. As in School Reunion, writer Toby Whithouse’s previous contribution to Doctor Who, shape-shifting fanged aliens are in charge of a school and are exploiting young humans. OK, so the Saturnynians use perception filters rather than actually changing shape, but the result is the same. The mysterious Silence has made refugees of the Saturnynians in much the same way that the Gelth in The Unquiet Dead were displaced by the Time War. As in The Curse of Fenric, the vampiric creatures are water-dwellers. However, Whithouse crafts clever explanations for characteristics that appear to resemble vampires, such as their fangs and their lack of reflection. This episode also sees the welcome addition of Rory (Arthur Darvill) to the TARDIS crew, following his introduction in The Eleventh Hour. His interaction with the Doctor and Amy effectively deconstructs the typical Doctor/companion relationship, particularly his accusation of the Doctor: “You know what’s dangerous about you? It’s not that you make people take risks: it’s that you make them want to impress you... You have no idea how dangerous you make people to themselves when you’re around.” The Vampires of Venice charts the reconciliation of Amy and Rory, from Rory’s initial shock when the Doctor tells him, in a comical pre-titles sequence, about “that kiss”, to his attempt at heroism and the reawakening of Amy’s love for him. Things don’t get too slushy, though, as the episode ends with the Doctor and Rory resigned to the fact that they are both Amy’s “boys”: “Yeah, we are.” Despite the fact that a romantic relationship is explored, things never really get “domestic” in the way that certain episodes did during Russell T Davies’s reign, because apart from a brief, minute-and-a-half stopover at Rory’s stag do (following three minutes spent at Amy’s house at the end of Flesh and Stone), the events take place in the midst of an adventure in another time and place. Like Rory and Amy, this episode and the Weeping Angels two-parter go well together (even more so now that there’s an additional bridging scene between them - more on that later), even though one is clearly dominant over the other. 6

It’s been five years since Amy and Rory travelled in the TARDIS with the Doctor. When he shows up again, on the eve of the birth of Amy and Rory’s first child, danger is not far behind. Amy is faced with a heartbreaking choice that will change her life forever... Many fans seem to appreciate Amy’s Choice far more than the two-part Silurian story that follows it. For me, however, the episodes are of a fairly consistent quality, as I will attempt to explain. Amy’s Choice is undoubtedly an enjoyable change of pace. It begins five years into Amy and Rory’s future, a jump made all the more believable by the precedent set by the Doctor’s inadvertent abandonment of Amy for a total of fourteen years during The Eleventh Hour. For the first few minutes, it seems as though the show has returned to the domesticity of the RTD era. However, it is then revealed that the 2015 timeline is just one of two parallel plotlines. Are the Doctor, Amy and Rory in the TARDIS dreaming about being in Upper Leadworth, or are they in Upper Leadworth dreaming about being in the TARDIS? Writer Simon Nye keeps us guessing. Though best known for his comedy writing, he injects plenty of drama into his script. Though there are comical moments, many of them involving Amy’s pregnancy and Rory’s ponytail, the level of personal jeopardy for the protagonists is particularly high, with the threat of disintegration by killer pensioners in one possible reality and the danger of freezing to death in the other. The imagery of the iced-up TARDIS interior is, if you’ll excuse the pun, truly chilling. Orchestrating these events is the Dream Lord, someone the Doctor has met before. I didn’t guess his identity: judging by his powers (godlike, in his own realm) and motivation (hatred of the Doctor), I thought he might be the Celestial Toymaker or one of the Guardians. In fact he’s the Doctor’s dark side, which sort of makes him an alternate incarnation of the Valeyard. Actor Toby Jones could easily have played the part entirely for laughs, like Q in many of his later appearances in the Star Trek franchise, or Superman’s nemesis Mr Mxyzptlk, but Jones often makes the Dream Lord decidedly menacing. One thing that lets the episode down is the nature of the alien presence in Upper Leadworth. Sinister residents of Amy’s home village, who reveal their true nature by opening their mouths? Aliens that appear in the form of frightening eyeballs? It’s like a combination of ideas from The Eleventh Hour. Having said that, perhaps this recycling of story elements is a deliberate clue to the nature of this world - and actually eyes, especially single eyes, prove to be a recurring motif this year. Another problem is the predictability of Rory’s fate. As soon as he stepped aboard the TARDIS in The Vampires of Venice, I expected him to be written out shortly afterwards, like Mickey Smith in Series 2. Nevertheless, his sacrifice and Amy’s reaction to it are dramatic and moving, and, though his condition “gets better”, it is in fact a cunning foreshadowing of things to come... Amy’s Choice is not without its faults, but for the most part it goes like a dream. 8

In 2020, the most ambitious drilling project in history is under way. Dr Chaudhry and her team have reached 21km into the Earth’s crust, but something is stirring far below. Amy discovers that there’s nowhere to run when you can’t even trust the ground at your feet... Well, perhaps it’s not the most ambitious drilling project in Who history, not if you take into account Professor Stahlman’s scheme in Inferno, and Torchwood and UNIT’s even more impressive drilling operations mentioned in The Runaway Bride and Journey’s End. However, those ventures were probably top secret, so Nasreen Chaudhry (Meera Syal) wouldn’t have heard of them. Alternatively, perhaps this is the most ambitious drilling project yet because the crust is so thick at this point - it does look like quite a hilly area. In addition to Inferno, The Hungry Earth also recalls another Season 7 story. I refer, of course, to Doctor Who and the Silurians, the story that introduced the reptilian foes that return in this two-parter. In fact, Chris Chibnall’s story is a veritable field day for fans of the Pertwee era, as it also features a small Welsh mining village (as in The Green Death), which is isolated from the outside world by an energy barrier (as in The Dæmons). The new, more expressive prosthetics used for the Silurians, a different subspecies from the ones we’ve seen before, are arguably closer in appearance to the Draconians in Frontier in Space, though the masks worn by the Silurian troops do bear a resemblance to the Silurians of old. Could it be that the creatures we saw in earlier stories were also wearing masks? This might explain actor Norman Comer’s blinking eyes, visible behind his Silurian mask, in Warriors of the Deep! The design styles of the old show are also evident in the warrior caste’s guns (which resemble the Sea Devil guns used in The Sea Devils and Warriors of the Deep) and uniforms (which reflect those of the Sea Devils in Warriors of the Deep). The Hungry Earth could have done with restating the fact that time can be rewritten in the Doctor Who universe, otherwise it may appear as though there’s no real threat to Amy and Rory, since their future selves are seen alive and well at the beginning of the episode. Actually, there was to have been a scene in which the Doctor and Amy discuss that very issue, but it was left on the cutting-room floor when the first edit seriously over-ran. Perhaps the scenes involving the future Amy and Rory should also have been cut, for reasons of clarity. As it is, the situation is made clearer in the next episode. Like Amy’s Choice, the opening episode of this two-parter isn’t perfect, but it sets things up nicely for a more effective part two... 7

The time travellers find themselves plunged into battle against a foe from a bygone age. The Doctor must face his most difficult challenge as he tries desperately to ensure that Alaya’s prediction of a massacre does not come true. Can Tony and his friends be trusted...? In Cold Blood, Rory, separated from the Doctor and Amy, really comes into his own, taking charge of the situation up top, tending to the injuries of Tony Mack (Robert Pugh), and effectively conveying sheer panic when it appears that his fiancée has been executed. However, it’s what happens to him in the final moments of this episode that really sticks in the memory, and both Darvill and Gillan give poignant performances. Series 5 has shown a structural tendency towards epilogues that deviate from the flow of the preceding narrative. Sometimes these codas are detrimental to the enjoyment of the episode, as is the case with the anti-climactic and over-long scenes involving Bracewell at the end of Victory of the Daleks. Sometimes they are genuinely moving, as is the case with the ending of Vincent and the Doctor (more on that episode later). Sometimes they raise eyebrows and are truly surprising, as is the case with Amy’s sexual advances at the end of Flesh and Stone. The climax of Cold Blood is both moving and surprising, with the sudden appearance of another crack in the universe, the fate of Rory (the predictability of which has been pre-empted and thus offset by its precursor in Amy’s Choice), and startling new evidence about who and what is involved in the explosion that caused the cracks... The episode also features a thoughtful performance by Stephen Moore (Marvin in the radio and television versions of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy) as the Silurian leader Eldane. The production team effectively swells the ranks of the Silurians, creating a convincing illusion of a vast underground city, populated by numerous revived citizens with many more still in hibernation. Sadly, the same cannot be said of the human population in this two-parter. The scale of the drilling operation seems small compared with that of Inferno (though to be fair the beginning of The Hungry Earth sees Nasreen sending most of her staff home for the weekend). The level of threat to humanity as a whole is undermined by the containment of the seemingly all-but-abandoned mining village, whereas the events in Doctor Who and the Silurians reach heavily populated areas, due to the infection of the civil servant Masters. The battle scenes are impressive, though the edit loses sight of Eldane, so it’s not immediately apparent that he has joined the humans. His siding with the humans and his solution to the conflict are both rather convenient. However, this is offset by the subsequent tragedy that befalls the TARDIS crew, which remains compelling viewing, even after the revelations that take place in The Pandorica Opens and The Big Bang. 8

The TARDIS travels back in time, but terror lurks in the cornfields of 18th-century France, and only a sad and lonely painter can see it. The Doctor and Amy join forces with Vincent van Gogh, but can the three of them defeat a powerful and deadly alien...? This year’s Doctor Who has made notable use of comedy writers. Perhaps this shouldn’t come as a surprise, given that Steven Moffat was previously best known for his sitcom Coupling. Writers this series have included Mark Gatiss (The League of Gentlemen), Simon Nye (Men Behaving Badly, How Do You Want Me?) and Richard Curtis (Blackadder, Four Weddings and a Funeral, Notting Hill, Love Actually), who penned Vincent and the Doctor. What is surprising is that Vincent and the Doctor is one of the most earnest episodes of the entire season. Yes, there are funny bits, such as the Doctor’s references to his two-headed, smelly godmother and jokes based around the time travellers’ foreknowledge of van Gogh’s eventual critical acclaim, but essentially this is a poignant salutation to an artist whose genius was not recognised in his own, tragically short, lifetime. Several of the artist’s paintings are referenced and/or brought to life on screen (in particular Wheatfield with Crows, The Church at Auvers, Café Terrace at Night, Bedroom in Arles, Sunflowers and The Starry Night), and the extended epilogue is real lump-in-the-throat stuff. It could be argued that the episode doesn’t really need a monster (it might be nice for the production team to tackle a purely historical story for once). However, but it can equally be argued that the Krafayis symbolises van Gogh’s inner demon, the then undiagnosed condition of manic depression, which no one else from his time can perceive. Scotsman Tony Curran is the embodiment of van Gogh in all but accent. His own Scots brogue is retained, covered by a throwaway comment about the Scottish Amy sounding Dutch to Vincent. It’s not very explicit for casual viewers, but I presume it’s a side effect of the TARDIS’s translation systems (like Phil Cornwell’s Cockney Roman market trader in The Fires of Pompeii). Less forgivable are the variable pronunciations of the surname van Gogh, especially from Smith, who doesn’t even try with his “van Goff”. Not quite a masterpiece then, but a memorable and moving work of art. 8

There’s a house on Aickman Road with a staircase that people walk up, but never come back down again. To solve the mystery of the man upstairs, the Doctor faces his greatest challenge - to pass himself off as a normal human and share a flat with Craig Owens... With scripts this year being contributed by the creators of Men Behaving Badly, Love Actually and Coupling, it’s ironic that The Lodger - the most romcom, sitcom episode of them all - isn’t written by any of those people. The principal guest characters, Craig and Sophie, are pure sitcom material, in terms of both their personality types - two friends who keep on utterly failing to reveal that they’re in love with each other - and the performers who play them - James Corden (Gavin & Stacey, Horne & Corden) and Daisy Haggard (Man Stroke Woman, The Persuasionists). Add to the mix an eccentric flatmate, and we could have the makings of a comedy pilot episode on our hands - though of course the Doctor is far stranger than any man behaving badly. There is a science-fiction element, in the form of the mysterious occupant of the upstairs flat, who is responsible for the disappearance of numerous passers-by and whose distortion of time is somehow preventing the TARDIS from materialising properly. The occupant is another variation on the theme of Prisoner Zero in The Eleventh Hour: both take on a variety of forms, but whereas Prisoner Zero hid his room from view by means of a perception filter, the occupant’s flat isn’t really there at all. The script is adapted by Gareth Roberts from a comic strip he wrote for Doctor Who Magazine, though the TV version is quite different. The strip had no mysterious man upstairs, and it featured the Tenth Doctor crashing at Mickey’s place - though in both cases the Doctor is separated from his companion and his TARDIS, and in both cases the Doctor disrupts his flatmate’s plans for a romantic evening. Whereas the comic had the sonic screwdriver being mistaken for a toothbrush, the TV episode has the Doctor mistaking Craig’s toothbrush for the sonic. There is no Doctor-lite episode this year, though The Lodger is decidedly Amy-lite, as the companion appears only in TARDIS scenes, interspersed throughout the episode. The Lodger certainly isn’t an unwelcome guest in my DVD collection. 8

After so many ominous warnings, including van Gogh’s final painting, the Pandorica finally opens - but the secret it holds is more terrifying than even the Doctor had anticipated. The fates are drawing close around the TARDIS. Is this the day the Time Lord falls...? The trouble with Doctor Who series finales is that each year the stakes are raised higher than before. At the end of Series 1, the Daleks returned and threatened the Earth in the far future. At the end of Series 2, both the Daleks and the Cybermen returned and threatened the Earth in the here and now. At the end of Series 3, the Master returned, conquered the Earth and threatened the entire universe. At the end of Series 4, Davros and the Daleks returned and threatened to destroy the whole of reality. At the end of the Tenth Doctor’s era, the Time Lords returned and threatened to end time itself. How could Moffat possibly top that? Well, by bringing back the Daleks, Cybermen, Autons, Sontarans, Judoon, Sycorax, Silurians, Hoix and Roboforms (also throwing in mentions of the Terileptils, Slitheen, Chelonians, Drahvins, Zygons, Atraxi and Draconians) and actually destroying most of time and space! Admittedly, most of these monsters appear only briefly at the end of The Pandorica Opens, and they are represented according to which costumes were available in good condition, rather than their importance to the show’s overall mythology (so we have the Hoix and Roboforms, not to mention some Weevils and the Blowfish from Torchwood, but no Yeti or Ice Warriors), but you get the idea. Rather more impressive are the ways in which this two-parter unites plot elements and themes from all eleven of the preceding episodes in the series. The Pandorica Opens visits the timelines of Vincent and the Doctor, Victory of the Daleks and The Beast Below, and marks the return of River Song, last seen in The Time of Angels / Flesh and Stone - and that’s just in the pre-credits sequence! There’s also a thematic connection with Victory of the Daleks, as the Auton Rory’s struggle to resist his programming and assert his humanity echoes the earlier depiction of Professor Bracewell. Rory, of course, reappears after being apparently erased from history in Cold Blood, re-created from memories like the dream worlds of Amy’s Choice. The Silurian two-parter is more obviously referenced in the presence of the reptiles among the alien alliance and in a brief flashback to prophetic moments from Flesh and Stone and Cold Blood. Finally, we make a return trip to Amy’s house, previously visited in The Eleventh Hour and Flesh and Stone. The presence of deep-cover and/or humanised Autons also echoes themes from previous Who stories in spin-off media, including the novels The Scales of Injustice, Business Unusual, Instruments of Darkness and Autonomy, and the audio drama Brave New Town. The Pandorica Opens is not without its faults. For example, this episode indicates that River Song is imprisoned in the 52nd century, whereas Flesh and Stone, in which she remembers the events of The Pandorica Opens, takes place in the 51st (though perhaps this is due to a complication in River’s timeline that has yet to be explored). It’s also hard to believe that no one notices the disembodied Cyber-head at Stonehenge, and it’s a shame that the creature uses the Borg’s favourite word “assimilated”, rather than the more traditional “converted” or “upgraded”. The Cybus Cybermen appear to have adopted conversion methods more typical of this universe’s Cybermen, adding mechanical parts to human bodies, as opposed to transplanting human brains into Cyberman shells (though in fact they’ve been falling back on this method since the events of Doomsday, as revealed in the Torchwood episode Cyberwoman). Nevertheless, The Pandorica Opens is a tremendously exciting penultimate episode. However, as Last of the Time Lords, Journey’s End and The End of Time - Part Two have all proven, creating a successful concluding episode is a much harder trick to pull off. How does The Big Bang fare...? 9

The Doctor is gone, the TARDIS has been destroyed in a temporal explosion, and the universe is collapsing. The only hopes for all of reality lie with a little girl who believes in stars, and a love that lasts for thousands of years. This is where it gets complicated... Like The Pandorica Opens, The Big Bang contains references to earlier episodes in the series. There are clips and newly recorded flashbacks to the events of The Eleventh Hour (with the return of the excellent Caitlin Blackwood as Amelia), The Lodger and Flesh and Stone. Rory’s dialogue recalls the events of The Vampires of Venice when he remembers that the Doctor “was the stripper at my stag,” and his resigned “Yeah, it is,” (after protesting that “I’m not Mr Pond. That’s not how it works,”) echoes his earlier “Yeah, we are.” Like the concluding episode of The End of Time, The Big Bang feels smaller in scale than its predecessor, due to its diminished cast and the rapidly shrinking bubble of reality. The alien alliance that threatened the Doctor in The Pandorica Opens is gone, save for a few stone relics, one of which comes back to life to provide some traditional threat. There’s a closer focus on the main characters here, with the love story between Amy and Rory reaching its pinnacle. As “the boy who waited” for almost 2,000 years for Amy, Rory puts Amy’s 14 years as “the girl who waited” for the Doctor in the shade. Darvill demonstrates his range as the usually bumbling and hesitant Rory gives way to self-assured bravery (“Do you think?”) and passionate rage (“She is to me!”). The Doctor’s testing of Rory recalls one of the earliest Who stories, The Daleks, in which Ian Chesterton goads a pacifist Thal into punching him. As with The Pandorica Opens, The Big Bang has its flaws. It is strange that there is no shorting out of the time differential (a la Mawdryn Undead) when the 21-year-old Amy touches the seven-year-old Amelia, especially when there is such an effect when the Doctor touches his sonic screwdriver to its temporal counterpart. However, this may be explained by cell renewal (over a period of seven to ten years, every cell in the human body is replaced, so the two Amys would not be composed of the same matter, whereas the two Brigadiers in Mawdryn would be, albeit partially) or the fact that the two Amys are from divergent timelines. The Doctor himself, being a Time Lord, is of course immune to such effects! I can just about accept that the whole universe can be extrapolated from a few billion atoms (this is, after all, established as the basis for the Total Perspective Vortex in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy) and that Amy, having been exposed to energy from the cracks in the universe for most of her life, can remember people back into existence via the power of the Pandorica. However, I find it a bit of a stretch that she is able to summon the Doctor back into being after the cracks have closed (indeed, were never open in the first place) and the Pandorica has been destroyed. It’s even harder to explain how the post-restoration River Song ends up on Earth in 2010 and seems able to remember Amy, Rory and quite possibly the Doctor, or at least is aware of their significance. With two poignant farewell scenes (excellent performances by Gillan and Smith) and a supreme act of self-sacrifice, this two-parter would have made a good regeneration story - but then that’s true of most Who finales. In The Parting of the Ways and The End of Time, the Doctor does of course regenerate. In The Stolen Earth, the Doctor begins to regenerate, but manages to halt the process in Journey’s End. The events of Last of the Time Lords also seem geared towards a regeneration, but instead the aged Doctor is rejuvenated by almost magical, pseudo-religious means. In The Big Bang, the Doctor is erased from reality, heroically saving the whole of creation at the cost of his own existence - which would have made a fitting end to the entire show, never mind the season. However, he is subsequently resurrected by a similar statement of faith to the one in Last of the Time Lords. It’s the sort of messianic depiction of the Doctor that I had hoped the series would leave behind when Moffat took over from RTD. I suppose this resurrection can be explained by Amy retaining some of her special qualities in the restored timeline. In any case, the “old, new, borrowed, blue” idea is a stroke of genius by Moffat, and beautifully articulated by Gillan. The domestic setting of the story’s conclusion is also a bit RTD, but before long the Doctor and his companions (the first married couple to travel in the TARDIS) are setting off into time and space again. Moffat has fun flouting the usual rules of time travel in Who, taking advantage of the collapse of the universe and the breakdown of its physical laws to allow the Doctor to enjoy some Bill & Ted-style antics with River’s vortex manipulator. For all my criticism of its narrative cheats and structural flaws (cracks in its universe, you might say), The Big Bang is, for the most part, an excellent adventure rather than a bogus journey, brimming over with crackling dialogue, emotive performances, and rousing music by Murray Gold. Bringing closure (the first truly happy ending of the revived series) while also promising further thrills to come at Christmas and in 2011, it makes a fitting end to Series 5 and an effective bookend to The Eleventh Hour. 9

Six of the thirteen episodes offer in-vision commentaries: The Eleventh Hour (with executive producers Steven Moffat, Piers Wenger and the lovely Beth Willis), Victory of the Daleks (with Mark Gatiss, Dalek operator Barnaby Edwards and Dalek voice artist Nick Briggs); The Time of Angels (with Steven Moffat and Karen Gillan), The Vampires of Venice (with Toby Whithouse, director Johnny Campbell and actor Alex Price), Cold Blood (with director Ashley Way, actor Alun Raglan and second assistant director James Dehaviland) and The Big Bang (with director Toby Haynes, Karen Gillan and Arthur Darvill). These are frequently amusing, especially when Gillan is involved. I don’t really mind the fact that not every episode has a commentary - lots of season box sets don’t. I am far more irritated by the lack of “next time” trailers, as previously discussed, though all the other broadcast and cinema trailers appear to be present and correct. The lack of deleted scenes is another glaring omission, especially in the case of The Hungry Earth, which reportedly had about a quarter of an hour trimmed from it. As usual for the complete series box sets, the Confidentials have been cut down to about 15 minutes each. Given the lack of commentaries, couldn’t BBC Worldwide have included longer versions of the Confidentials? All four of the ten-minute Monster Files featurettes from the single-disc releases are also present. There are roughly seven minutes of outtakes, though these comprise fluffed lines and behind-the-scenes fooling around rather than deleted scenes as such, as well as three video diaries, recorded by Smith, Gillan and Darvill respectively, which run to about ten minutes each. However, the highlight of the special features has to be Meanwhile in the TARDIS, two newly recorded three-minute scenes, written by Moffat and featuring the Doctor and Amy. The first takes place between The Eleventh Hour and The Beast Below, the second between Flesh and Stone and The Vampires of Venice. The presence of these scenes is probably the reason why the Weeping Angels two-parter is, slightly annoyingly, spread over two discs - so that the second Meanwhile in the TARDIS can be played between Flesh and Stone and The Vampires of Venice without changing discs. I’m sorry to bang on about this, but why go to the effort and expense of producing these very enjoyable additional scenes and yet not include the already recorded “next time” trailers and deleted scenes? Despite the relative lack of extras compared with previous box sets, this collection is essential viewing for all fans of the new, new Who. Richard McGinlay |

|---|