|

Click here to return to the main site. Blu-ray Review

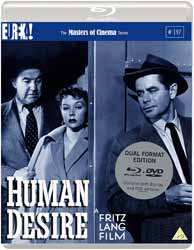

Extortion is the cancer of love. It metastasises love. Love flourishes. Extortion leeches. Unto death. Loving humans reduced to desperate beasts. Both, like twin railroad tracks, are grounded in Human Desire (1954), the title of Fritz Lang’s most penetrating humanist work of all his Hollywood fifties films. (Partial list — Rancho Notorious [1952] Clash By Night [1952] The Blue Gardenia [1953] The Big Heat [1953] While the City Sleeps [1956] Beyond a Reasonable Doubt [1956]. Human Desire is perhaps best of all of Lang’s films ever. Cry havoc and let the arguments hurl. Lang’s filmic precursor is the Jean Renoir classic La Bête humane (1938) eponymously titled after its own precursor, the novel by Emil Zola written in 1890. Lang keeps the railroad settings from both but opts for a Hollywood ending where love wins out over consumptive evil, in this case, self-respect and the thing we call honour, chosen over the inconsolable despair of the beast. Though let it be said, a Langian Hollywood ending is not sweetness and light but haunted with industrial strength noir. We must thank Eureka Entertainment (eurekavideo.co.uk) for its steely grey, coldly perfect 1080p Blu-ray dual format (Cat. # EKA70329) of this B&W masterwork from the imminent DP Burnett Guffey (Knock On Any Door [1949], All the King’s Men [1949], In A Lonely Place [1950], The Sniper [1952], From Here to Eternity [1953], Mr Sardonicus, Homicidal [1961], King Rat [1965], Bonnie and Clyde [1967]). Both Renoir and Lang open with subjective rolling shots of a locomotive engine burrowing headlong down its determinate tracks, plunging through pitch black tunnels, bursting into daylight for the experience of zoning out from destiny. This opening is a friendly familiar feeling for Lang fans, remembering his lingering love of the industrial world of the fishing industry in the first shots of Clash By Night (1952). Humans work in these machines. The machines always know what to do and where they’re going. Not so the humans. This is, after all, the director who gave us Metropolis (1927) so we shouldn’t be surprised at his perennial question: what does it mean to be human? - to be more than a beast inside a robot? Is this a question for those of us locked inside a technoid-virtual reality today? Forget I mentioned it. Hitchcock thought of himself as some sort of philosopher. Compared to Lang it’s a pale conceit. Thematically and cinematically Lang is the superior artist. Hitchcock is a trickster in framing, composition and cutting. Lang is a professor of questing humanism. Hitchcock is the little boy who was once locked in a jail cell and told ‘that’s where all bad boys go.’ Lang was a man who was offered total control of the finest industrial film machine in the universe (by you know who) and walked away from it for an honourable destiny, reminding us the people inside the machines still have a choice. This was the triumph of his will and it shows in his films like Human Desire. Glenn Ford is Jeff Warren, young locomotive engineer just returned from a war everyone was told wasn’t a real war, in Korea. This is a shade above returning from a war that nobody even knows existed or cares to know, but his kinship with all soldiers home from the hill is established in a stroke. He’s hungry to be outside himself. Hungry for love. Not unlike the police detective he played for Lang a year earlier in The Big Heat (1953) whose beloved wife is blown up by the syndicate machine’s car bomb meant for him. Each character is confronted with aloneness. One with love snatched from him, the other with love not yet, if ever, realized. A Glenn Ford bi-polarity. Near the tracks another story is boiling over: yard boss Carl Buckley (Broderick Crawford) and his estrogen oozing wife, Vicki (Gloria Grahame) are coming apart. Carl knows he’s ugly, older and… bestial compared to Vicki’s beauty and barroom-stopping charisma. He’s perpetually suspicious of her. Is her slutty reputation past tense or still operating covertly? Both actors are Oscar winners. Carl is in crisis. He’s been fired for being an a*****e once too often yet he evokes our pity even as we judge him. It’s hard to hate the unpleasant when they know they can’t shake their givens. Vicki does have a heart under her perfumed décolletage so when he begs her to help him get his job back, to make a plea to a railroad executive, Owens (Grandon Rhodes), she finally agrees. Carl knows there’s been a past history and warns her not to go too far. She bristles at his double tongued desperation and bullying, his schizophrenia of male hypocrisy. Owens gets a sleeping car appointment with what he thinks will be an assignation but instead is Carl and death. Jeff Warren is riding the same train as a deadhead to get back home and becomes a potential witness so Carl has Vicki distract him. Jeff falls for her. Hard. At the inquest of Owens’ murder, he keeps his mouth shut. It becomes a roundelay of extortion vs love, a ménage à trois of need, human desire the cleaving sticky glue of orgasm and blood. But the most erotic scene in this buttoned down fifties vision is Vicki alone, lying on the living room floor to reach up into an air shaft for stolen money and an incriminating love note. Grahame’s spread open legs, her arching back up to her straining face, clutching for the stash, must have made Lang happy. Especially her look when she gets hold of it up in the wall. I know it made me happy. When the good woman (Kathleen Case) who loves Jeff comes to his giant engine idling in the railyard, she asks: ‘Can I come up?’ He answers: ‘You’ll get yourself dirty.’ Alfred Hayes wrote the finely tooled screenplay and I’m sure Lang approved every syllable. For those who don’t know Lang, this is an excellent way to get acquainted. 10 John Huff Buy this item online

|

|---|