|

Click here to return to the main site. Blu-ray Review

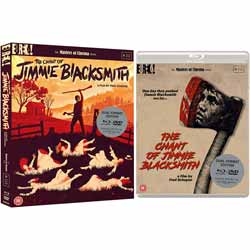

From his debut on the stage of world cinema, Fred Schepisi distinguished himself as a genuinely humanist director. He never followed the crowd. The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith is his second feature after The Devil’s Playground (1976) which was about, what else, a young man struggling for meaning in a Catholic seminary. Jimmie Blacksmith is a young bi-racial aboriginal whose struggle is for more than meaning but life itself, in a hopelessly bifurcated culture ruled by Anglo-colonial overlords. (youtube.com/watch?v=aOpV3r12a3Q). In less than ten seconds, social bifurcation is established by Schepisi in his first two shots: 1) an opening shot of aboriginals working, while their children play, in a fetid farm compound, dirty, squalid; This is the world Jimmie Blacksmith is growing up in. He is a studious young man, learning to read and write and compute arithmetic. He will grow up (Tommy Lewis) and try to make a place for himself and his bi-racial family as Australia emerges from the 19th into the 20th century. Jimmie is described by his own people as a ‘paley bastard’ and ‘mongrel man’ and by most whites in writing and speech, as a n*****. Tommy Lewis is an ‘eye’ actor giving us an inside-out view of his humanity through the windows of his soul. Schepisi tells in an interview, (in one of the best Special Feature troves this fan has ever seen, so don’t snivel about the RRP, this Dual Format disc is worth every penny) how he delineates acting talent between ‘performance levels’ and ‘acting levels.’ The difference is remarkably clear throughout (compared to average movies where acting is reduced to indicating) with his excellent cast of aboriginal naturalesque talent (highlighted by Lewis, Freddy Reynolds and Steve Dodd) and Australians (Jack Thompson, Angela Punch-McGregor, Bryan Brown and an early appearance by Lauren Hutton). It is an illuminated joy to hear Schepisi talk about how he extracts interior performances from his outstanding cast. We are reminded that the merits of great movies are measured by intangibles. Humanity. Based on the book by Thomas Keneally (author of the book behind Schindler’s List, 1993) one realizes Schepisi is a listener, a collaborator, enjoying the challenge of heavyweight creators, working for the ineluctable ‘feel’ that only a novel can give. Keneally must have agreed because he appears in a cameo as a horn-dog ambidextrous cook, going for a stand-up nooner, while he’s still at work at his barnyard stove. This to assure us he was not an absentee to the collaborative confab. Jimmie is cheated mercilessly by his bosses, his good natured Protestant work ethic rubbed into the mud. He revolts. The bloodletting in these scenes includes a lightning coup de gras, searing into our heads how impulse ignites the escalation of violence. Even hardy fans of genre gore will gasp, not because of the strong practical effect but because of its psychological ambush in a domestic setting gone crazy. (No spoiler, me.) Comparable – in social conflict, time setting and based on true incidents – to the American film, Tell Them Willy Boy Is Here (1969) directed by the then recently un-blacklisted Abe Polonsky, we are in the socially conscious seventies, a period of brave filmmaking yet to be replicated in our starvation era of Comic Con wankery. (It is interesting to hear Schepisi tell of being blacklisted during his foray in Hollywood because he’d had the temerity to walk off a grandiose nothing burger movie after explaining to studio nut-sacks, he just couldn’t do it, he couldn’t live with that beast for over a year. How dare he? So he was banished from the kingdom of Sunset Boulevard.) Both Jimmie Blacksmith and Willy Boy are archetypal Anglo revisionists’ scrutiny of manifest destiny: the drubbing of autochthonous people, who in traditional Darwinian wisdom, lack ‘civilized Christian values’. Both films show what the pioneer west was really like, American and Australian. Jimmie Blacksmith is in every way the superior film. Schepisi, no doubt mining Keneally’s novel, takes great pains to give us a perception of aboriginal lore and code of conduct, its nobility, its ancient heritage of passionate respect for the cosmos of animistic being. It is a beautiful culture, in harmony with both land and mantle of sky above. We may not comprehend the chant of Jimmie but we do understand its mainstay value for him, as sure as the turning of the earth. Cinematography by Ian Baker is worthy of masterwork appellation. Landscapes and how people of different castes fit in them is its own commentary, harmonious with the succinct script, propulsive editing and sensitive directing. Eureka Entertainment is to be commended for its studious technical shepherding to bring this work of art to us in all its force, its glory and… humanity. 10 John Huff Buy this item online

|

|---|