|

Click here to return to the main site. Blu-ray Review

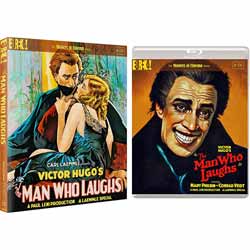

Conrad Veidt’s image in The Man Who Laughs has resonated beyond his lifetime and influenced other creators not only to pay homage to the look but also to the psyche of Veidt’s groundlaying characterization. Director Paul Leni’s master collaboration with Veidt may be the most pivotal persona of twentieth century film and well on its way to the same archetypal status in our century. To say the various incarnations of The Joker are drawn from Paul Leni’s original image created for Carl Laemmle’s Universal Pictures in 1928 begs a lot of questions. Bob Kane, Bill Finger and Jerry Robinson openly acknowledged their inspiration for The Joker in their 1940 Batman comic (DC Comics, Batman #1 April 25, 1940) that introduced the character. I say along with the iconic look comes an intrinsic bundle of questions that excavate beneath surface presentations of comic book, camp television and movies. There’s something about the face that makes actors become Oscar winners or die in the attempt. Put on this face and look in the mirror. Are you still there or has the face taken over? Jack Nicholson said the role was haunted. I believe him. The Man Who Laughs is where the haunt started. The Conrad Veidt face is a hybridized synthesis of our bi-polar dramatic proscenium: tears and laughter, compacted into concrete simultaneity. Leonard Shlain, in The Alphabet vs. the Goddess, his masterwork on brain function -- masculine and feminine neurological values and how they reflect and enforce culture -- would deem this a left lobe perception. If so, it has a confounding and mesmerizing effect on right lobe linearity, sequential worship, reductionist and abstract superiority. Paul Leni distilled this impactful face from the Victor Hugo novel (The Man Who Laughs) and transubstantiated for the world its visual impact. Leni, working with makeup genius Jack Pierce and art director Charles Hall and the brilliant Veidt, forged a collaborative work of genius. All under the permissive reign of studio demi-god, Carl Laemmle. Eureka is right on in lauding this collaboration as foundational for the Universal horror landmarks that were yet to come. And Zeus status for its incarnation by Veidt. In 17th century England, Gwynplaine is a carnival sideshow performer. As a child his face was mutilated by fiends working for his father’s enemies, professional child mutilators. Human slime. He grows up to work in a carnival, a favourite of groundling peasants and a curiosity for slumming royals. He loves the blind Dea (Philbin) and though she can’t see him, Gwynplaine believes he is unworthy of her love. He dares not let her touch his face, his ever-present smile. When Queen Anne discovers his noble standing, he must choose between a return to a life of privilege without Dea or The Tower. There are Machiavellian villains in the court who see Gwynplaine as a pawn to embarrass the Queen. There is also a beloved wolf dog, sort of a proto-Rin-Tin-Tin, named Homo (no jokes, though this dog is straight romantically) played by actor dog, Zimba. Zimba is devoted to the sightless Dea and sees himself as sort of a child of Gwynplaine and Dea. Zimba performs protean services in the denouement and finishes by swimming while wagging his tail. (I’ve been very good here I’ll have you know, not to go spoiler.) Silent films are often ridiculed for their histrionic acting. By 1928 this case is hard to make for we sophisto moderns, especially with The Man Who Laughs. Veidt is limited to conveying the truth through his eyes, brows, forehead and posture. The limitation only increases respect for his instrumental talent. You don’t need inter-titles or dialogue to read his thoughts. He is a dramatic genius. “It is precisely as if I’m possessed,” he said, “by some other spirit when I enter a new task of acting as though something in me presses a switch and my own consciousness merges into some other, greater more vital being.” It is his eyes in contrast to that continuous grin, the dichotomy of pain to laughter, that make this one of the great performances in film history. Or as the sightless Dea puts it, “It’s wonderful how my Gwynplaine makes people laugh even when he’s sad.” The surface of the film is a delight, feels like looking at a multi-shaded conch shell. Frame composition is a discourse on that art. Lighting is apotheosis German expressionism. (All are testaments to director Paul Leni and his trusted cinematographer Gilbert Warrenton, A.S.C., art director Charles Hall and make-up supervisor, the legendary Jack Pierce). Movement by individuals and crowds is balletic. Rhythm of editing (by no less than Edward L. Cahn) is as timeless as anything from any era. All movies today should express their grammar of film so well. Restoration was conducted by Universal Pictures from a 35mm composite fine grain print from the studio’s salt mine archives in Kansas. Final restoration was provided by NBCUniversal Post. There are two music tracks to choose: the original Movietone soundtrack from studio orchestrator of the day, Joseph Cherniavsky and a new composition form the Berklee Silent Film Orchestra laid down in 2018. I don’t want to hurt feelings here. But the new score sometimes leans into elevator music and its adult contemporary tropes don’t work for me. (They should have consulted with a soundtrack musicologist like David Shecter. Just sayin’.) It’s like a really good paint job on a concourse class automobile but not the model colours, not even funky. The Movietone track is raw, raspy, tinny at times and dated, at first, for about thirty seconds but suddenly you’re back in Universal horror land, same orchestra, same tropes, same sincerity of passion. I buy the Movietone, hook, line and baton and am grateful Universal gave me the choice. It transports me back to the first time I saw the Universal horror package on television, Frankenstein, Dracula, The Invisible Man. This score is their Ursus from the cave. For those who wonder about director Paul Leni. He died soon after the film wrapped. He was riding high with Laemmle and Universal, having completed The Cat and the Canary the year before, again working Gilbert Warrenton lensing. (youtube.com/watch?v=Wl9p-GWDbI8&t=1920s.) Some historians say he never got to see the finished cut of The Man Who Laughs. Conrad Veidt went on to reinvent himself in sound pictures, always glad to play Nazis, whom he despised. His most famous Nazi is Major Heinrich Strasser in Casablanca (1942). He was the highest paid cast member at $5,000 per week. He died on Hole Eight of the Riviera Country Club in April, 1943. Of course he is known for playing the fiend in the original Cabinet of Caligari (1919) but less known for his tour de force Hitchcockian thriller by Powell and Pressburger, Blackout aka Contraband in 1940. He’s funny, romantic and suave, volley for volley with a wise talking Valarie Hobson. Worth checking out: youtube.com/watch?v=c0e7aFkqYFE The Eureka Masters of Cinema Series includes Kim Newman, horror film expert extraordinaire, on the formative influence of Paul Leni. The Face Deceives, a doctoral degree dissertation video essay by David Cairns and Fiona Watson. Paul Leni and The Man Who Laughs, a great historical grounding on Laemmle, Leni and the Universal singularity by John Soister. The Stills Gallery: Production, Behind the Scenes, Costumes / Make-up Tests, Exhibition / Trade Ads, first run Programs, Posters, Heralds and Memorabilia. If you buy only one silent classic for your home library. This is it. 10 John Huff Buy this item online

|

|---|