|

There's

no doubt that Doctor Who is as much an English institution

as fish and chips and inclement weather. Its influence has

reflected on many generations, but what has influenced Doctor

Who? Like James Bond it needs to conform to certain

strict criteria. There can be next to no character progression,

except perhaps to recall and learn from past events. The Doctor's

reaction to new and even hazardous situations is childlike

wonder or, on occasion, religious reverence.

|

Ah,

now there's something... Passive religion has had a profound,

though referred, effect on the programme's history. Let's

begin with Time Lord society, which appears to be based heavily

on ceremony. Elaborate robes, hierarchically divided according

to school-house-like chapters and designations, along with

regalia and an air of serene superiority are surely connections

to the church. Having discovered a manner in which to traverse

time, they now see themselves as lords over it. They have

strict laws of time and a policy of non-intervention in the

affairs of other societies, which could be said to be a Godlike

wisdom of allowing people to learn from their own mistakes

(though they think nothing of unleashing the odd bolt of lightening:

removing someone from existence itself, forcibly regenerating

the Doctor, or even the attempted termination of him to save

themselves).

The Black Scrolls and The Ancient Law of Gallifrey

contain "forbidden knowledge" of the dark times; forbidden

because no society wants to remember its failures. So they

exist as a reminder to only the elite, like the downbeat sections

of The Bible which seek to investigate the dark side of the

human psyche. In fact, it was rumoured at one time that an

earlier form of what became known as The Bible existed in

the Vatican. It was said to conflict drastically with the

later writings and contain such horrific events that it was

not fit for the world, religious or otherwise, to behold.

Everyone likes to be frightened, say the experts; it's good

for the soul. The horror element is an integral part of the

Doctor Who mythos, but like all monsters they are only

original reflections of the legends of ancient cultures and

perhaps one of the oldest horror books of all (whether it

be truth or fiction), Revelations, from The New Testament.

|

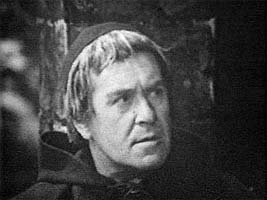

Aside

from the Doctor, there are a few other so-called renegade

Time Lords. One such example is the Monk, played by Peter

Butterworth in two William Hartnell stories, The Time Meddler

and The Daleks' Masterplan. As the character's motives

are far from religious it can only be assumed the robes were

worn to enable him to more readily infiltrate and manipulate

the peoples of religious societies. His robes of false-office

allow him to come and go, unchallenged, from an empty monastery.

Such is the church's status in this time-line that he is actively

aided by the locals.

Before

the backdrop of Time Lord society had been established on

screen, the War Chief was seen as a reckless, argumentative

antithesis of the official Time Lords themselves, who serenely

acted as self-appointed judge, jury and executioner, even

though they were said to have that non- intervention policy.

If a classroom full of obedient zombies has one individual

who is prepared to question what is being taught, then is

that student viewed as being a disruptive influence or an

original thinker? Clearly, we are steered towards believing

the former of the War Chief - for good reason - and the latter

for the Doctor, although they are somewhat similar in their

unorthodox methods and treated as such by the self-important

Time Lords. It's indicative of the power the church once commanded,

even to the detriment of royalty, and the influence from the

past it retains to a lesser extent today.

|

When

the Master entered the picture only a couple of years later,

his mannerisms were gentlemanly in all but his aspirations.

Aside from the formal exterior lending greater effect to his

inner intent, it was also a throwback to that strict formal

society. Witness the third Doctor's harbinger of doom in Terror

of the Autons, looking for all the world like a city toff.

In fact, Hartnell's and Pertwee's portrayals are much more

in keeping with that formal bearing: the air of no-nonsense

authority over pompous bureaucracy being tantamount to the

reason why the Doctor escaped the confines of Gallifrey in

the first place. Class is the obvious link to western culture

religions here; even a lowly priest in the middle-ages enjoyed

certain courtesies and privileges.

|

The

interior of the Doctor's TARDIS in the series is generally

clean and brightly lit, almost to the point of purveying a

sterile atmosphere. Its inferred vastness is cathedral-like,

as evidenced in the fourth Doctor story, The Masque of

Mandragora, wherein Sarah Jane catches a glimpse of the

boot cupboard. This cathedral architecture is prominent in

the Paul McGann TV movie, even to the point of stained-glass

windows. The central column of the time rotor descending from

the high ceiling exaggerates the grandness, as does the plainly

monastic look to the TARDIS library. Temporal grace, a particularly

religious term, prevents weapons being discharged inside.

This reflects from the church's preaching

of pacifism, which is ironic as more wars through history

have raged in the name of religion than anything else, barring

perhaps land itself. There

are cloisters, as evidenced in Tom Baker's final story, Logopolis,

and a cloister bell which chimes as a portent of doom in the

same manner as a church bell once signalled a journey to the

gallows. The TARDIS can travel to any point in time and space,

which in my book is the closest a person can come to omnipotence;

to travel to different time periods and not be affected by

its passage you must surely have to be outside of time itself,

a godlike position.

Although

reluctant to open a veritable can of worms by relating a popular

family-viewing televisual experience to the teachings of the

Bible, can there be any greater compliment than to compare

such a successful and workable premise and expanding format

to the greatest story ever told?

Most

significantly, let's turn to the character of the Doctor himself.

The most remarkable trait is his Time Lord ability to regenerate

his dying body (reincarnation, anybody?). Twelve regenerations

(that's thirteen bodies) are possible, and whilst not being

true immortality, a careful Time Lord could conceivably live

for thousands of years. The seventh Doctor was over 950 years

old, and you could hardly call him careful!

|

The

Doctor always sides with the underdog against oppression in

the face of great adversity. This is exactly what Jesus Christ

achieved, and like Jesus the Doctor has the charisma and conviction

to walk into a situation and instantly command attention,

gaining converts to his pleas for justice - the former under

constant threat from the military might of the Roman empire,

and the latter amidst mad scientists and alien invaders. A

first Doctor historical adventure was set at the time of Roman

dominance. Although no one noted it at the time, the generally

light- hearted direction of the story retrospectively prevented

any comparisons being made (except by me, of course!). Admittedly

Roman influence was wide-spread and spanned many years, but

it's worth pointing out nonetheless. And talking of Romans,

the paragon of "When in Rome, do as the Romans do" doesn't

appear to be a code of conduct as far as the Doctor is concerned.

Time Lord arrogance again? Self-preservation in the face of

forced sacrifice to some unknown deity is one thing, but we

have witnessed many pagan-like rituals being played out in

Doctor Who, and our hero always attempts to avert the

so-called "atrocities" rather than accepting that this is

their everyday way of life... their beliefs. It is the age-old

trap of one religious order trying to stamp out another, rather

than accepting a difference of opinion and getting on with

life.

In the same manner that some sceptics might write off miracles

as illusion or technological wizardry in the face of anachronism,

the Doctor has managed many death-defying manoeuvres. Jesus

was seen to have died on the cross, and yet pulled off the

greatest escape from a sealed tomb, to be seen alive again

later by witnesses. The Doctor has often seen to be dead,

only to be saved by his increasingly astonishing physiognomy:

two hearts, a respiratory by-pass system, the ability to lower

his heartbeats considerably and even enter a self-induced

healing coma. As for the disappearing act, well, TARDISes

are supposed to contain a chameleon circuit enabling them

to blend in with their surroundings, thereby rendering them

invisible to the untrained eye. It's almost as if Doctor Who

creator Sydney Newman and his subsequent associates sought

to logically rationalise those historical events in terms

of believable fiction. However, it would an outrageous conceit

for anyone to claim that this was all intended from the original

concept; particularly because background detailing has been

added over the years - often for the sake of convenience -

to flesh-out the central character and situations as much

as it is possible within the constricting parameters.

|

Jesus

had his disciples, and the Doctor's companions are not too

dissimilar in their motives. No matter how they come to be

TARDIS crew members they soon realise the Doctor always struggles

to do the right thing (not always the lawful thing) and will

not turn his back on a situation where he can make a difference.

In fact, the Doctor will protect his travelling companions

with his life, never hesitating to make decisions of self-sacrifice

when warranted. Jesus demonstrated the greatest sacrifice

of them all; so too the Doctor. After all, the act has the

same importance whether it be on behalf of one or many. Perhaps

the best example of this is when the fifth Doctor and Peri

contract the fatal disease Spectrox Toxaemia. The Doctor struggles

in a weakened condition to the lower levels of the caves to

obtain the bat's milk antidote, but only recovers enough for

one person; Peri is his first consideration. For the fifth

time the Doctor regenerates.

|

However,

there was one very different companion. Turlough was the Judas

Iscariot of the Doctor Who world, betraying the Doctor's trust

and in this case even attempting to kill him several times.

Turlough was found to be under the influence of an entity

known as the Black Guardian (a case of the Devil made me do

it!). This neatly brings me back to the Master, if we can

return to his shenanigans for a moment. This evil renegade

character was originally brought to the programme as a Moriarty

to the Doctor's Sherlock Holmes, but he is better suited as

a Satan to the Doctor's messiah. In the same way that the

Fallen Angel was banished from Heaven, the home of Jesus,

the Master is a Time Lord and also comes from Gallifrey, making

him conceivably the ultimate living nemesis. He is a perfect

opposite to the Doctor, and like the sixth Doctor's adversary

the Valeyard, epitomises the dark side of us all.

So

there you have it, reasonably brief and to the point; the

influences (purposeful or not) are there if you look in the

right places. Doctor Who borrows from only one place for its

theme, making it one of the most original, flexible and therefore

enduring ideas ever devised for TV family viewing. In the

face of increasing adversity over the years, curiously including

dissention in the ranks - or, perhaps, more accurately described

as "leading from the back" - it is truly remarkable that Doctor

Who has thrived for so many years, albeit nowadays in so many

other forms. A miracle? Perhaps. Now all we have to do is

pray for its TV return!

Return

to...

|